Why Celebrating the "Power of Print" Can Be a Mistake

Regular public disclosure of newspaper print circulation ended in 2013, but last year was apparently so bad some publishers are now revealing a bit more

Welcome to Second Rough Draft, a new newsletter about journalism in our time, how it (especially its business) is evolving, and the challenges it faces.

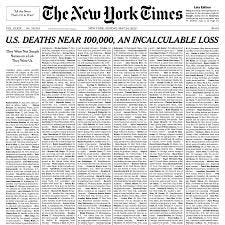

Every few weeks, it seems, I see on Twitter or cable TV someone celebrating a newspaper front page, usually with a reminder about the unique “power of print.” Then I almost invariably notice that the person making this point works at a newspaper or used to do so. And they aren’t wrong—like most things in journalism now, the best print design is the best there ever was. But print, by any reasonable definition, is losing its power, for the simple reason that, Twitter and TV screenshots aside, it is disappearing.

Most of the folks celebrating print papers know this, and the tone of the text accompanying the screenshots is often the same as nostalgic references to the pony express, or defiant paeans to wooden tennis rackets. Yet, the problem goes deeper than that, I think, because emphasizing the power of print is, at some level, a rationale for denying, and perhaps trying to retard its fate.

So I thought this week we might try to stare the facts in the face. Many are well known. Here are a few that may not be:

The most indicative may be that print circulation numbers for newspapers in this country stopped being generally available in 2013. (!) Since then, they are available only through a pricey subscription generally taken only by advertisers.

Very few newspaper companies are publicly traded these days, and even those that are (those controlling the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, the Gannett papers and a few others) omit print circulation numbers from their earnings releases. The stock analysts that follow these companies are so focused on digital growth that they don’t demand the information.

Nevertheless, if you dig a bit, you can piece the numbers together (although, as one pretty good indicator, the latest on Wikipedia— which reflects the deaths of celebrities within minutes— are from 2019). In particular, last year seems to have been so bad for print circulation that at least a few public-company publishers are making additional disclosures.

In many cities on many days there no longer IS a print newspaper. These include Cleveland, Detroit, Little Rock, Pittsburgh, Portland, Maine, Portland, Oregon, Salt Lake City, Spokane, Syracuse, Toledo and a host of smaller cities.

Five years ago, in writing about this, I had some fun at the expense of a McKinsey report from late 2015 that said,

We believe that many of the people likely to abandon print newspapers and print consumer magazines have already done so…. We believe most of this core audience — households that have retained their print subscriptions despite having access to broadband — will continue to do so for now, effectively putting a floor on the print markets.

As I guessed, that hasn’t aged well.

Let’s take the example of the New York Times, the most successful “newspaper” business left in this country. At the time of the McKinsey report, its individually paid average weekday circulation[1] was about 525,000, down perhaps 25% from when circulation stopped being publicly reported just a bit more than two years before that. By the beginning of last year it was reportedly down to 410,000. The Times’ earning report last month said it fell another 14% last year, which would put it at about 350,000—that is, down about one third from the “floor” called five years ago by McKinsey, and less than half that last public report in 2013.

Not just the Times

In case you think I’m picking on the Times (and I’m not—again, they are the market leader), let’s look at the Wall Street Journal where, 17 long years ago, I was the assistant publisher. Just before the McKinsey report, its individually paid circulation averaged 1,060,000 copies, also down about 25% since the end of public reporting. By the beginning of last year it was, by the same report cited earlier, just below a million, a relatively modest decline of six percent. But if you do some math from numbers reported in parent company News Corp.’s recent earnings release, subscriptions now number just 777,000,[2] which makes it highly unlikely that Journal print circulation exceeds 900,000, down at least 10% in the last year. The numbers for most metropolitan papers around the country, the majority of them now in the hands of hedge funds, are not disclosed at all, but are almost surely worse.

Why does this matter?

In my view, because of the nostalgia with which I began. If you see the print newspaper as more than the pony express or a wooden tennis racket, you are likely to invest scarce intellectual and perhaps even financial resources in trying to preserve or maybe even revive it. Precisely because those resources are scarce, that will be a waste.

Print newspapers are a product for which we need managed decline. Moreover, we need to bear very much in mind that they were a classic industrial era product in which profitability came from economies of scale—the first thousand copies were very expensive to produce, the last thousand relatively quite cheap. As any such product declines, there comes a point at which profitability not only declines rapidly, it turns into loss. Where, as with “newspapers,” there is an available substitute (in this case, digital) offered by the same manufacturer, the best course at that point is to work to accelerate the decline, transitioning those customers who can be moved, and eventually parting ways with the rest.

For newspapers, that time, in many places, is drawing nigh. Telling ourselves stories about the “power of print” in such circumstances may not be doing any of us any favors.

[1] This is the key number, combining print subscribers and single-copy sales. It omits bulk and free copies, which often aren’t reflective of consumer demand. It does not include Saturday-Sunday circulation, which, in many cases, is fading more slowly, but that’s a subject for some future newsletter.

[2] Here’s the math: News Corp. says that total Journal digital subscriptions are 2,460,000, and that digital subs are 76% of all subs. That means there are 3.24 million total subs, and 3.24 million less 2.46 million gives you the 777,000 figure when un-rounded. My allowance of newsstand sales at 20% of that is quite generous historically. Given the collapse in newsstands, even before the pandemic, my best guess is that the real individually paid circulation figure is about 850,000, which would be a decline last year roughly in line with that at the Times, and a decline since the McKinsey report five years ago of more than 20%.

My @LenfestInst colleagues and I agree with Dick Tofel on the perils of over investment in print. I've attached here a link to a Nieman article I wrote late last year about the need to accelerate "stopping the presses" (eliminating print) at major metro newspapers in order to realize their full and promising digital potential: https://www.niemanlab.org/2020/12/a-newspaper-renaissance-reached-by-stopping-the-presses/