Why Are Social Media Policies So Hard for Newsrooms?

In setting rules, it makes sense to go back to the reason we need them.

Welcome to Second Rough Draft, a newsletter about journalism in our time, how it (especially its business) is evolving, and the challenges it faces.

Social media policies for working journalists have proven a quagmire for news organizations. Some are overly restrictive, undermining staff morale, inhibiting recruitment and likely restricting audience growth. Others appear arbitrary, or least seem to be applied arbitrarily, which can be unjust, sapping staff and reader trust. Some, to judge by the output of more than a few reporters I see in my timelines, may actually be too permissive.

Having watched newsrooms and the people who work in the them wrestle with this problem for more than a decade now, it seems to me that too much energy has been put into crafting specific rules and too little into recalling why we might want them.

Social media posts—particularly on Twitter, where much of the problematic material from reporters seems to end up—actually are just a newish way to get yourself into an old form of trouble.

Let’s Start With the Policy

In about 1997, I rewrote the old Dow Jones & Company Conflicts of Interest Policy to create a more modern Code of Conduct for the company that, then and now, owns the Wall Street Journal.[1] A decade later, as we were founding ProPublica, I borrowed heavily from this work, and that of others at AP, Time Inc. and the Washington Post, to craft a Code of Ethics for our new shop. With everything that has changed in the last 14 years, we haven’t felt the need to amend it. So the following, written almost a quarter of a century ago, still seems very much on point:

“it is an essential prerequisite for success in the news and information business that our customers believe us to be telling them the truth. If we are not telling them the truth – or even if they, for any valid reason, believe that we are not – then [we] cannot prosper. [We] will suffer, for example, if our customers cannot assume that… our analyses represent our best independent judgments rather than our preferences”

That is, Twitter posts create a problem if a reasonable reader might find there something that would make them believe you won’t be fair in your news coverage. It’s pretty much that simple.

What That Means In Practice

This means, for instance, that reporters are entitled to much less latitude in expressing reasonably contested opinions about things they cover than other material.

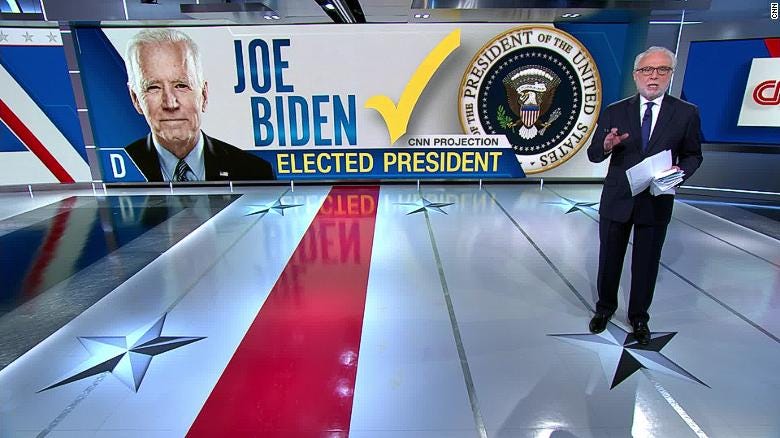

Let’s unpack that sentence a bit. First is whether a particular opinion can be reasonably contested. So, I see no issue with a political reporter tweeting about how Trump lost the 2020 election— contentions to the contrary are not reasonable. But that is no justification for someone covering elections, for instance, expressing opinions about the merits of particular proposals for partisan gerrymandering—or even about whether partisan gerrymandering is constitutional or unconstitutional. (I have strong views on this myself, but acknowledge that, as just one example, a majority of the Supreme Court feels otherwise.)

Second, it follows from the general rule that journalists should have much more latitude to express their preferences outside the subjects they cover or may cover. What possible difference does it make if a health reporter condemns partisan redistricting?

Focus on Reasonable Readers

Do we really believe that reasonable readers are prepared to impute the opinions of everyone at a large organization to the organization as a whole? I doubt it. Many of those readers, now or in the past, have worked in large organizations. They know better. Even if a few readers are prepared to hold news organizations to account for the views of hundreds or thousands of people with no responsibility for a story, do we really want that unreasonable viewpoint to set policy for us? If not, should it make any difference if a large group organizes to advance the unreasonable perspective?

On the other hand, we do need to bear in mind that social media endures (“there’s always a tweet…”). So if today’s health reporter aspires to be, or just might become tomorrow’s elections reporter, they should govern their conduct accordingly. And people within newsrooms with supervisory responsibility, or those who hope to wield it someday, will find that a wider range of restrictions are in order than those who have found their niche and plan to remain.

The Question of Personal Experience

What about personal experience with a subject? In many cases, this can deepen a reporter’s ability to appreciate a subject and convey both its importance and nuance. So personal experience should not be an automatic disqualifier from coverage, nor a forbidden zone on social media. But if experience has left a reporter more nearly an advocate, as it quite understandably can, then that reporter should direct their reporting efforts elsewhere.

At the same time, we shouldn’t want somehow to get ourselves, individually or institutionally, in a position where we are reluctant to tell people what our reporting has shown, or to remind them of it as often as may be necessary. Indeed, the more some people try to pretend that the facts are other than they are, the more we may need to redouble our own efforts. That’s true both on social media and elsewhere.

Most important, let’s go back to first principles, back to the need to avoid giving the impression that our judgments are really just our preferences. What we need isn’t new social media policies but sober decisions applying enduring values.

[1] The Code has been revised, most recently in 2012, but much of the previous language remains.