What Can We Learn from the Near Death of the Texas Observer?

It’s not the only news nonprofit on the brink- and there will likely be more

Welcome to Second Rough Draft, a newsletter about journalism in our time, how it (often its business) is evolving, and the challenges it faces.

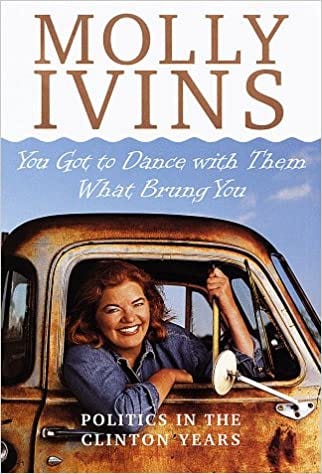

Last month, the Texas Observer, a nonprofit magazine with a distinguished history, most notably including the work of Molly Ivins and Ronnie Dugger, had a near-death experience. Its Board suspended publication before reversing itself in the face of a GoFundMe campaign.

Along the way, the Board chair and the chief fundraiser resigned, and it was revealed that the magazine had essentially spent its entire reserve and apparently misspent its largest grant, while the GoFundMe, even at nearly $350,000, brought in only enough to cover about 12 weeks of spending—assuming the Observer ends its print edition and lays off three of its 17 staff as part of a 30% budget cut.

I don’t come this week either to praise the Observer or to bury it, but rather to try to learn from what appears to have happened there. I want to do this because the Observer is far from unique. It is not, for instance, the only well-known news nonprofit currently hanging by a thread, while others have recently failed. Given the precarious macroeconomic outlook, it’s easy to imagine that more nonprofits are or will soon be on the brink.

Here are some of the lessons I think we need to heed from the cases of the Observer and others:

Nonprofits are sustainable, but only if managed for that

This sort of management is the responsibility of both the staff and the Board. Both are responsible when a company fails. At the Observer, effective management was no doubt made much more difficult by turmoil that included churning through six top editors, temporary and permanent, over the last four years. A shared responsibility for management for sustainability requires, for instance, that information on finances must be regularly, fully and candidly shared. And then the information requires people’s attention.

Previous understandings may need to be re-visited—that’s part of how all organizations evolve. The Observer staff was likely correct that the magazine needed to adapt to a changing audience. (Texas was 61% non-Hispanic white in 1970; now that number is 40%.) But by the same token, a publishing company that is bleeding revenue probably can no longer afford an historical aversion to advertising and sponsorships.

Reserve funds are for emergencies, not business as usual

It’s best practice, when feasible, for a nonprofit to have at least six months of spending, and ideally a year, in a liquid reserve. The big question that arises if you can amass such a fund is when and on what to spend it.

The answer is that the reserve is there for emergencies. A recession is the classic example; history shows that these occur from time to time, but are relatively short. Spending down part of a reserve to get through such a downturn without layoffs (or at least too many of them) can make great sense. (But if you got PPP loans in 2020 and 2021 and saw them forgiven, those funds should have been exhausted before invading a reserve, or used to replenish the reserve if possible.)

Alternatively, the emergency may be organizational, rather than societal. A newsroom may be dealing with costly departures or bad publicity or some other transitory issue. Or it may have an opportunity to make a capital or other expenditure that will trigger new growth. But secular decline in revenues or audience or both is not an emergency—it’s a strategic problem—and trying to deal with it by spending your reserve only delays the day of reckoning, and makes things worse later. In the Observer’s case, the Texas Tribune reports, 90% of the available reserve was spent over the last two years, ahead of last month’s crisis.

In the long run, a fundraising Board is essential

After more than 18 months in my new incarnation as a consultant, teacher and columnist, I feel even more strongly than I did when I was a nonprofit news manager that—absent some huge endowment-- there is simply no substitute for a fundraising Board. Large numbers of small gifts are wonderful, and heartwarming, and affirm the mission, but small numbers of large gifts are also critical, and actually make up a greater part of total revenues for nearly all successful nonprofits.

I understand that not all newsrooms can muster a Board with this focus at the outset, but it seems to me an essential objective as soon as feasible. Board members who are contributing meaningful amounts of money seem to pay closer attention to how that money is being spent, which is an indispensable Board function. And Board contributors are generally both more willing and more able to help raise other revenues.

It also seems increasingly apparent that the converse of a fundraising Board is one dominated by journalists and former journalists, very few of whom are in a position to make large gifts. Make no mistake: some of my best friends are reporters and editors, and every Board responsible for a newsroom should have sufficient knowledge and experience to recognize and safeguard journalistic independence and integrity. But this should require just one or two current or even former news professionals (plus a group willing to listen to them).

With respect, I just don’t agree with the current editor of the Observer that Boards consisting mostly of journalists can solve nonprofits’ problems. Nor do I think that analogizing the business of nonprofit journalism to that of organized labor makes sense. Yes, both are causes, and movements. But labor unions are funded mostly by their own workers— and thus need lots of them paying dues, often amalgamating the workers of many companies. News nonprofits are often small, fiercely independent, and need to pay their workers living wages, ideally competitive wages as well.

Mergers may be an answer, but at least one party needs to be acting from strength

No merger that I know of has been suggested in the case of the Observer, but this does seem to be a solution being mentioned more and more often in response to newsroom revenue challenges. In general, as I’ve said before, I think that’s a good thing. But successful mergers will rarely if ever flow from mutual weakness. At least one of the parties needs to be proceeding from some sort of strength. As you will recall from elementary school, negative one plus negative one does not equal two.

The possible loss of a publication like the Observer is a tragic story. It can also be a moment for reflection, and learning. We can all be heartened that the Observer’s readers stepped up with some interim relief when the magazine was threatened. But we would do even better if we took stock of the reasons that the Observer was endangered in the first place— and applied them elsewhere before it is too late.

+1 with bells on to EVERY. SINGLE. WORD. You (kindly) chose not to lay any responsibility at the feet of nonprofit journalism funders (including me) here, so please allow me to do the honors. (I come neither to praise funders nor to bury them/us, but rather to try to share what I have learned, often the hard way, since I have started doing this work.)

Funders of nonprofit journalism have a lot to answer for when it comes to the landscape you have described: a lot of newsrooms and news organizations are in very fragile shape. In my experience, funders get dazzled by -- and often only evaluate -- editorial output and editorial aspirations; too seldom do they (we) look "under the hood" at the state of the organization itself, not only before a crisis but, inexplicably, during and after it as well. (Full disclosure: I used to be one of those kinds of funders; I didn't know any better.)

Now, let's look at how funders can do better, and in doing so, better support the field by helping to strengthen it for the long haul. As aforementioned, funders should look under that organizational hood to assess both the financial strength and stability of the news organization and -- and this is key -- the strength and stability of board governance. In situations where what's under the hood is pretty strong, funders, in my opinion, should either provide more general operating support and/or, in the case of restricted grants, provide a generous amount for indirect costs (funders should insist that this be in the grant budget, sending the message that they understand that executing successful projects isn't "free"). Over the course of the grant, funders should talk to the organization not only about the editorial, but also about financial and board capacity; stay on top of it, and, if necessary, be open to shifting the use of grant funds if an organization that is generally well managed and governed hits an unexpected rough patch.

Okay, now we move on to the more common situation, where, while not yet an existential crisis, what is under that hood doesn't look so good. The reasons can be any and all of the things you have cited as flags that an organization is vulnerable. In that situation, a funder can help by providing funds not for editorial projects alone (or at all), but for what might be called capacity-building. Part of good grant-craft is working with the organization to identify, discuss and, most important, figure out ways to solve for the weaknesses under that hood. Are the financials kind of messy? Is the board unclear about its responsibilities? Is there not a finance committee (I've seen this more than once in a nonprofit news organization)? Presuming the funder has not decided to abandon ship (which might be the right decision in any given situation), that funder can be immensely helpful by funding and suggesting, for example, a short-term consultant to help right the ship. Or, by funding a non-editorial staff position such as development director, or audience manager -- roles that build strength and stability. Such a grant can and should include specific benchmarks, mutually agreed-upon, that concretize the goals of the grant. In my experience, some organizations will initially chafe at this degree of funder "direction," but ultimately, they appreciate the results and say so. The organization is stronger, thus the field is stronger. (And, by the way, I also think it is perfectly okay to discuss this with fellow funders.)

Finally, we have the worst-case scenario: the collapse. The financial statements whose ink is red, the board that is neither giving nor raising money, the spend-down of reserve funds where the emergency is self-inflicted and most likely a long time in coming... it's usually a combo platter of problems. Funders are often asked -- pleaded with -- to step in with emergency funds. And, some do; nobody likes to see their grantees fail. And so, the crisis is averted -- for about 10 minutes -- because, in too many cases, nobody -- not the organization-in-crisis, and not the funders -- has tried to do an autopsy, to figure out and be honest about what went wrong, and then, to use the time the rescue grant has provided to do whatever is necessary to prevent the same thing from happening all over again. Any funder who steps in with rescue money and does not insist on this kind of autopsy is, in my opinion, just enabling the organization to walk itself right back up to the brink.

you forgot to mention that the Texas Observer is a left-wing magazine