Uvalde and Law Enforcement’s Credibility Gap

The lesson: no institution deserves a pass on journalistic skepticism.

Welcome to Second Rough Draft, a newsletter about journalism in our time, how it (often its business) is evolving, and the challenges it faces.

Before the disasters of Vietnam and Watergate, the press, by and large, took presidents’ account of events as presumptively accurate, and largely as reportable as fact without confirmation. That is to say, we trusted presidents to generally tell the truth. After Vietnam and Watergate, while what presidents say remains, by definition, newsworthy, the presumption of truth has been rebutted, trust withdrawn. While the result makes it harder to wield power to salutary ends, which can be frustrating, it also tends to curb abuses, as the Framers would have wished.

When this transformation was occurring, in the 1960s and 1970s, the phrase used to describe it was “credibility gap.” Today a consensus seems to be emerging that law enforcement in this country is suffering from a growing credibility gap of its own, of which the early misinformation (at best) put out after the massacre in Uvalde is the latest, and perhaps starkest example.

Right off the bat, it’s important to say that many people, including notable journalists of color, have been saying for years that police accounts, like those from other authorities, should not be taken at face value. And opinion research has long revealed that trust in law enforcement varies by race, age and partisan affiliation, with people of color, younger people and Democrats less inclined to trust police.

That said, and even after the murder of George Floyd, trust in law enforcement remained the majority view among the public. This placed police ahead of politicians, the press, big business and the courts, although behind small business, the military and science. Many journalists, not surprisingly, reflect this in their work.

It is early days, but Uvalde, it seems to me, could accelerate a change in these views. And it should.

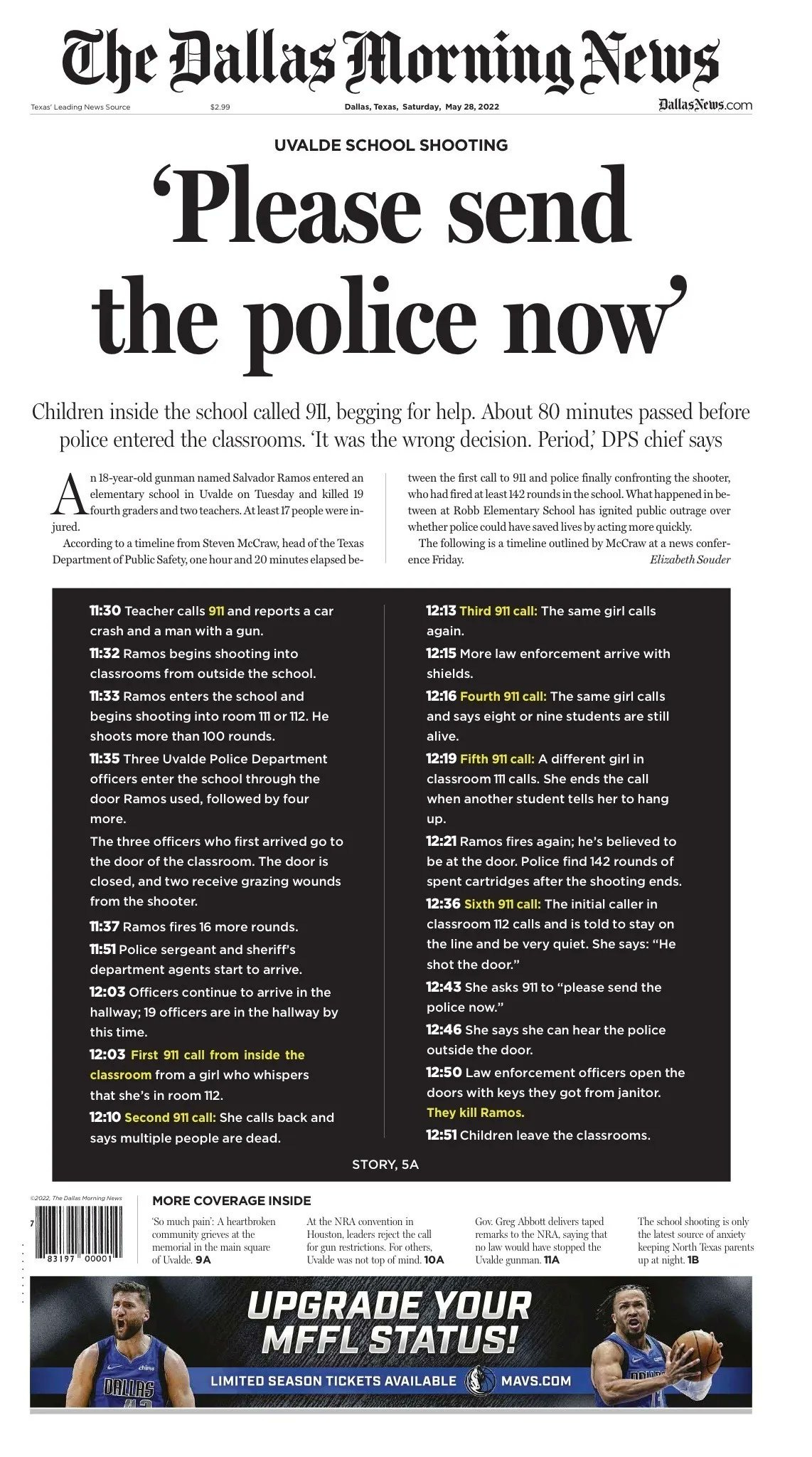

In simplest terms, the horror of Uvalde was also a major police failure. The facts are astonishing: 19 officers standing in a hallway outside the classrooms while, over 40 minutes, six 911 calls come from children inside. It appears that one to three children, and possibly many more, might have been saved by a more courageous and competent response. This follows a similar, if less dramatic, police failure at Parkland in 2018, as later investigations conclusively demonstrated— and more than two decades after the documented shortcomings at Columbine. And that is the larger point: Uvalde was an extreme case, but not unique.

As a society, and as journalists, we need to acknowledge that a number of things can be true at once: First, the majority of law enforcement officers serve honorably and courageously. Second, being human, some don’t, employing unnecessary deadly force, abusing their power or failing to rise to the challenge of sudden, dangerous moments.

When a failure occurs, and especially when innocent people die as a result, it should stop surprising us that institutions’ instinct is to misdirect, obfuscate, even misinform. Journalists know that this happens across any spectrum of organizations, and there is no reason we should expect law enforcement to be an exception.

What to do about it?

Especially in a world of ubiquitous cellphone video, we need to accustom ourselves to giving meaningful consideration to multiple accounts of events from the very outset. Yes, of course, hear out the police. But particularly if witnesses offer conflicting accounts, suspend early judgment on which view is likely valid. As with all reporting, place great weight on contemporaneous and first-hand accounts over later and second- or third-hand versions. Take videos, audios (including 911 calls) and other documentation seriously, especially if authorities suggest you discount them.

And—while the press has gotten better about this in recent years—try hard in fast-breaking and unexpected situations not to rush to even preliminary judgments about what has happened, and show a greater willingness to admit your own uncertainty.

Beyond those particulars, it is time— long past time— that we learn that the values of journalistic skepticism need also to apply to law enforcement, as they long have with people in other positions of even greater power and authority. This is no sign of disrespect for police or the necessity of professional policing. It is an integral part of the press doing its job.