Tough Questions for Google, and Thoughts on How We Got Here

A confrontational interview prompts reflections on the recent history of the news business

Welcome to Second Rough Draft, a newsletter about journalism in our time, how it (often its business) is evolving, and the challenges it faces.

This newsletter is called Second Rough Draft because a variety of people over the years have indicated that journalism is the first rough draft of history, and I hope here to reflect on both the business of journalism and the history of our time as it unfolds.

I have a special interest in the history of journalism, and have tried to write directly about that elsewhere from time to time, including in a biography of one of my heroes and an account of the crucial early days of our current era. I haven’t written much here about the history of journalism, but a recent interview has prompted me to make an exception this week.

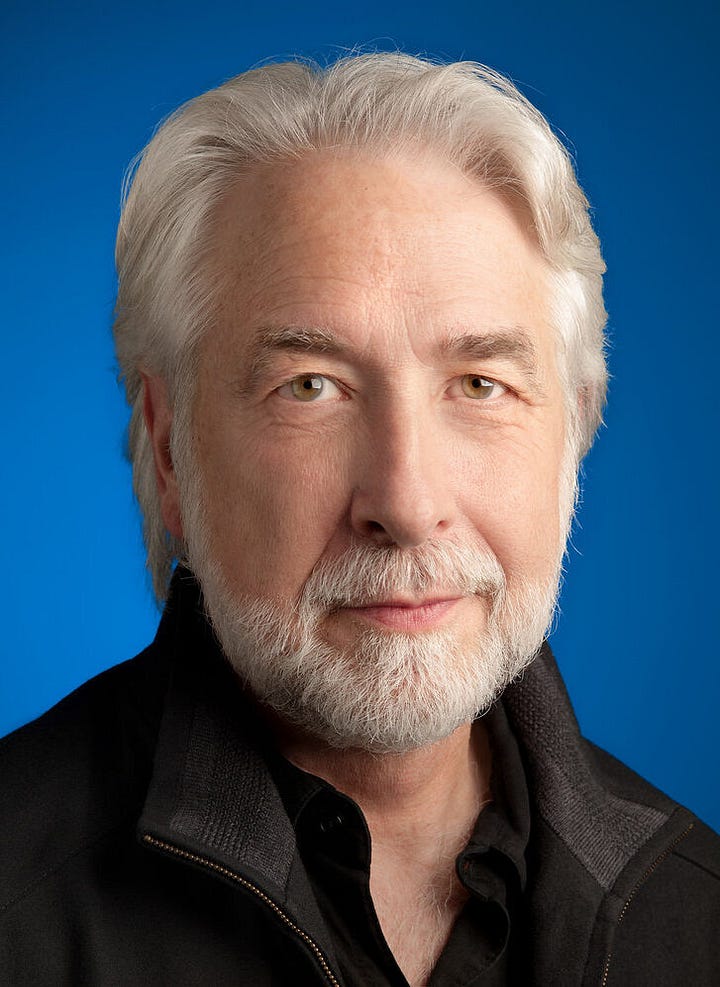

The interview was with Richard Gingras, longtime VP, News at Google, recently retired, and was conducted by Natalia Antelava, chief of Coda Story, at the International Press Institute World Congress in Vienna in late October. It was published (with an extended introduction by Antelava) by Coda Story earlier this month. If you have not yet read it, you should.

A confrontational interview

A disclosure up front: I have known Gingras for well more than 10 years and Antelava for more than a year, and regard both as friends. That’s a bit awkward, because the interview was confrontational and heated, and feelings are bruised as a result, with a dispute about what the groundrules had been and whether Antelava was unfair in her approach or appropriately holding power to account, whether Gingras had been ambushed or had engaged in what one reader called “obfuscatory generalities.” But none of that is what really interested me, and I am going to put it aside.

What I instead found fascinating was Antelava’s strongly revisionist take on Google’s role over the last two decades in and around the news business, and Gingras’s response to that.

I was particularly struck by the following exchange in the published interview:

Gingras: We were trying to do the right thing. Does that mean we didn’t make mistakes along the way? Of course. Like, you know, search ranking is the mission.

Antelava: What would you say was the biggest mistake you made at Google?

Gingras: I would say the biggest mistake, honestly, was in our work with the industry, the Google News Initiative. We spent over a billion dollars over eight years, a billion and a half dollars trying to drive innovation.

Antelava: A tiny line in the budget.

Gingras: Whatever. Who else around the world was spending anything close to that, trying to drive innovation in the news industry?

Unfortunately (as she now acknowledges), Antelava didn’t follow up on this, and the discussion moved along. Did Gingras say that GNI was a billion dollar-plus mistake? I asked him. At first, he responded, “I said no such thing.” He continued, “I NEVER said GNI was a mistake. She asked about what I might have done differently and that I said that I had wished we had put more focus on opportunities in local advertising, which I only later learned… was a significant opportunity that many are missing. That was it.” So I asked for and listened to the tape of the interview; the transcription is accurate. I asked Gingras to explain.

He pointed out that later in the published interview, he said this: “The things that I feel like we didn’t-- I don’t think we drove enough innovation. I, frankly-- one of the missing points that I thought we didn’t drive-- we spent a lot of time working with people to drive subscription growth. We missed, actually, what I see now is a significant opportunity is to drive-- particularly local news organizations-- to rethink what local advertising could be in their communities, right?” I have again listened to the tape, and, while the transcription is again accurate, I have cleaned up the punctuation of the passage quoted just above for greater clarity.

So now we’re pretty clear on what Gingras thinks. He added in a note to me, “I wished [GNI] drove true innovation, which frankly, was not as much about the GNI efforts, but more about the struggle of the industry broadly to innovate.” But I don’t think he’s right about what, in retrospect, was the problem with GNI.

The real problem with ‘We’re from Google and we’re here to help’

Sure, greater innovation would have been useful. But the real shortcoming was on the part of the many in journalism who actually thought Google was unselfishly trying to help. In retrospect (and even at the time), it seemed clear to me that GNI was a marketing exercise, an important way especially to distinguish Google from its rival Facebook. Facebook was sanguine if it was undermining the news business, as it was sanguine trying to destroy anything in its profit path, from commercial rivals to democracy itself.

Google wasn’t necessarily malignant, but it wasn’t unselfish either. (The same may be true today of OpenAI, journalism’s latest big corporate benefactor.) It’s not a coincidence in my view that GNI effectively ended at more or less the moment greater regulatory threats began to emerge in the US, as they had earlier elsewhere, and Google was adjudged a monopolist in the search business by a federal court. I have gotten the distinct impression from any number of Googlers that they regard the press as having been distinctly ungrateful for the billion-plus.

How we got here

Having said this, I want to be clear that I don’t agree with those who would contend that Google (or Facebook or Craigslist, for that matter) destroyed the business of journalism. Take classified advertising as a first, and simpler, example. The web itself transformed classified from a fundamentally print-based local business to one more efficiently and effectively run online and nationally or even globally. One or more newspapers might have seized this opportunity, and had a head start and ample available capital to do so, but when they did not, Craigslist did.

Internet advertising more generally presents a more complicated situation, but ultimately an analogous one. The medium offers material opportunities to those who can operate at huge, previously undreamed-of scale, permitting them to target marketing messages much more cost-efficiently than was possible in print or broadcast, and to offer marketing vehicles to literally millions of new customers. The five companies that eventually won the race for the requisite scale, Google, Facebook, Amazon, TikTok and Microsoft (currently in that order), now account for about two thirds of all online advertising. That is an oligopoly if ever there was one.

Again, news organizations might have entered this market in a way they did not. In the year 2000, the Wall Street Journal, where I then worked as an executive, published almost a billion dollars worth of advertising. That was far more ad revenue than Microsoft, then the leader among the emerging digital players. The total revenue for Google that year was $19 million; Mark Zuckerberg was still in high school; Amazon wasn’t yet seriously in the ad business. To achieve the requisite scale, publishers would surely have had to considerably broaden their offerings. That was an option, even if not widely perceived as such at the time.

So Google didn’t kill the news business, but nor did it seriously try to save it. Its support for news was both convenient at the time and now has been largely withdrawn during American democracy’s moment of maximum danger. It’s CEO stood shoulder to shoulder with the controlling shareholders of Facebook and Amazon behind Trump at his inauguration.

We will likely need a third and fourth rough draft of history before we can begin to reach even tentative conclusions about what to make overall of Google and the other platforms’ role in the fortunes of journalism, but it is surely soon enough to be asking hard questions.

Second Rough Draft will be off next week. Happy Thanksgiving to you and your loved ones.

Very helpful insights, and I thank you for them.

I watched the news industry decline throughout my career as the market research manager at a regional newspaper. Our parent company, Times Mirror, simply didn't find a way to invest in technology, to understand people's needs, and to work together with others in the industry to survive. (Times Mirror and Knight Ridder had tried videotext in the mid 1980s without success. Phone lines couldn’t offer enough capacity, and every newspaper’s system was unique, I believe. The internet changed everything.)

I heard that Times Mirror in the mid-1990s invited a well-known consulting firm to submit proposal to pay households so the firm could install video cameras in their homes (with their permission). Then the consultants would monitor what people watched and read throughout the day. But the cost was millions — and the study was never conducted.

Now, of course, Google Analytics can tell us what people watch and read, how long they spend with each story or video, where they come from and where they go. So newspapers were trying to determine readers’ wants and needs, but they didn’t find a feasible way to do it. Google did. And then to monetize the audience by targeting advertising.

I'd liken GNI money to a free Narcan prescription doled out by Purdue Pharma.

I got a GNI grant. I was grateful. But the problems we were tying to solve with the Google money were the problems Google itself had created.