The Journalism Lesson I Learned on September 11

Why the most effective preparation for a crisis lies in empowerment

Welcome to Second Rough Draft, a newsletter about journalism in our time, how it (often its business) is evolving, and the challenges it faces.

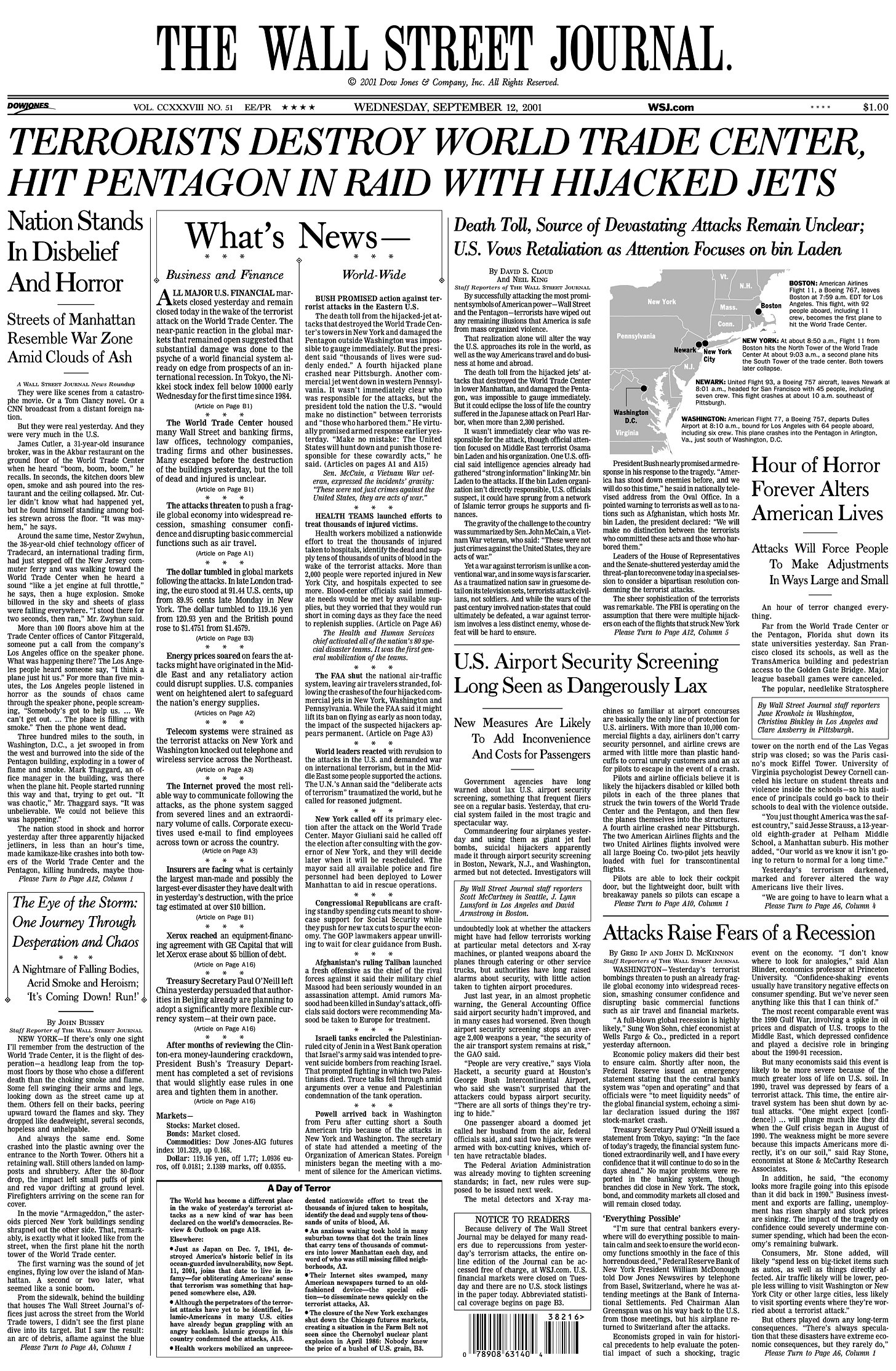

Almost exactly 24 years ago to the minute this is being published, I was rounding a corner in Lower Manhattan, walking to my Wall Street Journal office at the World Financial Center from the subway, and heard the first plane slam into the North Tower of the World Trade Center. It was about 250 feet away horizontally and 1000 feet up. I heard but didn’t see the impact in the starkest illustration I’ve ever experienced of the difference between the speed of light and the speed of sound. By the time the sound of a jet close overhead and then the explosion reached me and I immediately looked up, the plane had pierced the building, disappearing, and flames and debris were billowing out.

The day that followed was unforgettable, of course, and deeply tragic. Our family lost a good friend, the father of a soccer teammate of my daughter’s, and also among those lost were loved ones of dear friends I did not yet know and some I did. My memories of September 11, I have found, differ from those of most Americans then old enough to recall because I saw nothing on television until about 11:30 that evening, and then only from a hotel room near Princeton, New Jersey, close to the corporate offices from which we had just published the next day’s edition of the Journal.

Their finest hour

People seem to recall 9/11 as a day of terror and horrific loss, followed by the onset of endless wars. What has been mostly forgotten, I’m afraid, is how unified the country felt immediately afterward. But none of that is what I want to talk about this week. Instead, I want to recall why it was perhaps my proudest day at work in 38 years of full-time employment, and what I think I learned that day about journalism.

The Journal’s headquarters was catty-corner to the Trade Center complex, and we had to abandon it immediately after the second plane hit the South Tower, about 500 feet away. Some people had made it to work (foolishly proceeding after the first impact, I was one of them); many others were still on their way in at that relatively early hour for a newsroom.

Cell phones in the area didn’t work—the antenna supplying service had been located atop the Trade Center. For hours, the whereabouts of some key people, including my friend and once-and-future-boss, managing editor Paul Steiger, were unknown. My then boss, the publisher, was at a company celebration of the 25th anniversary of the Asian Journal in Hong Kong. It took us four days to finally determine that, nearly miraculously, we had lost no one from the Journal or its parent company; sadly, in the fullness of time that has proven no longer true.

In the end, all of the obstacles were surmounted. The paper was published from a back-up facility in New Jersey we had luckily tested not long before. The Blackberrys we had recently deployed among Journal staff proved invaluable.

There were individuals whose work from that day stands out, and I could name at least some of them here, but I’m not going to do that, and for an important reason: because doing so would start to miss the point.

The lesson

The point—the great lesson I learned that day—is that well-run organizations run best when everyone knows their job and feels empowered to do it. That is what happened at the Wall Street Journal on Tuesday, September 11, 2001.

Editors, in New York, Washington and elsewhere, gathered themselves, issued instructions and managed seamlessly through an evolution of leadership as the day unfolded. Reporters identified stories, sifted through what they could learn and wrote quickly and, in at least a few cases, beautifully. An editorial page team that happened to be in the middle of a generational transition of management produced a stellar report.

Dozens of people made their way toward Princeton because they knew that was where much of the work beyond reporting and writing needed to be done. Production managers figured out how to produce a paper starting much later than usual, circulation staff crafted and executed a plan to deliver September 12 copies in Manhattan north of Canal Street even as bridges and tunnels had been generally shut down. IT staff swung into action building out a temporary newsroom in New Jersey, initially by buying scores of computers at retail on a day almost all businesses closed early. Advertising staff managed the delicate issue of which marketers would still want their messages in the next day’s paper, and which would not. Corporate staff began creating a temporary headquarters we would end up using for a year.

In all of this, there were very few meetings and almost no memos or top-down instructions. Nearly everything happened on the fly, and with a remarkable sense of calm. There was important work to be done, and hundreds of people simply did it.

One of my most treasured possessions is an engraving of the production report from that night, indicating that 1,970,262 copies were printed across the country between 9:18 pm and 2:09 am Eastern Time. (In this, I know I am recalling an earlier era; the print circulation of the Journal is now less than 475,000.) Months later, the Pulitzer Prize Board awarded the Journal the Prize for Breaking News Reporting. Among its many accolades, the Journal had not won that prize before, and hasn’t since.

Preparing for the unforeseeable

If we are lucky, most of us will never experience first-hand a day like September 11. But in the news business, momentous and unexpected events happen from time to time at all levels of our work. You can try to plan for them in some ways, and to some extent—and you should. The most critical preparation, however, comes in the day to day, the clear assignment and delineation of responsibility, the instilling of common purpose and understanding of mission, the empowering of human beings to do their best work and motivating them to want to do it.

Today seems like a good day to remember that.

Nice remembrance, Dick. Much thanks.

Great column dick.