Welcome to Second Rough Draft, a newsletter about journalism in our time, how it (often its business) is evolving, and the challenges it faces.

This is my first column of the fifth calendar year of Second Rough Draft, and it continues a modest tradition of looking forward, and focusing on some of the journalism I’d like to see in the year ahead.

Like many of you, I am worried about what’s in store with the return of Donald Trump to the presidency. I also think the coverage of those prospects so far leaves a good deal to be desired, but perhaps not in the ways you might expect. In particular, I hope we can be both more discerning and disciplined along a number of dimensions:

Revolution or reality TV?

Distinguish between the truly revolutionary and the merely performative. Here, the issue of abortion from Trump’s first term (and thereafter) may be a useful yardstick. If, a decade ago, you thought the strategic goal of the “pro-life” movement was to overrule Roe v. Wade, you would likely consider Trump a revolutionary figure—he named Supreme Court justices who got it done. But if you thought the goal was to reduce the number of abortions in America—which hasn’t happened—you wouldn’t.

Moreover, Trump seems to have abandoned most of the movement’s key tenets—he has urged Republicans to embrace exceptions to state bans for rape, incest and to protect the life of the mother, has indicated he does not favor a federal limitations statute and stated six-week bans are too short (although he did personally vote to uphold one in Florida). His otherwise-dangerous choice of Bobby Kennedy for HHS is hardly consistent with a move against abortion pills.

When you put all of this together, the failure of abortion to be a key issue with voters in the last election should be less surprising than many found it— history may tell us that the “pro-life” movement won the battle on Roe but lost the war at the polls in 2022, and voters in 2024 may have understood this better than many pundits. (This is not to deny that some states are still fighting what we may come to see as rear-guard actions, and that those moves have very real human costs.)

I rehearse this contemporary history because I think we need to bear it in mind as other issues, such as immigration, play out. If Trump passes a version of last year’s border bill—which he blocked for electoral reasons, and which Kamala Harris endorsed—and declares victory over illegal immigration, that won’t be revolutionary. And if he accompanies it by a limited number of performative immigration raids, particularly targeting those with records of criminal violence, that won’t be revolutionary either, no matter how noisily it is done (and again acknowledging the human cost). Conversely, if he does actually undertake the deportation of millions of people, that will be revolutionary, and should be covered as such.

Similarly, if Trump continues to call loudly for the prosecution or persecution of his political enemies, that—no matter how offensive-- is far different from actually lodging criminal charges or otherwise bluntly employing the instruments of government to punish the innocent. And laying rhetorical claim to other countries, or parts of them, is weird, but it’s also merely rhetorical. I’m not saying, pace John Mitchell, that we should ignore what Trump says, but our coverage will serve readers better if it focuses closely on what he does (or doesn’t do).

Two echoes of a week long ago

Watch out for fearing fear itself, but beware a Reichstag Fire moment. Six crucial days in early 1933 offer two moments we should bear in mind in the months ahead. On February 27 of that year, amid the global Great Depression, the German Reichstag (parliament) was the target of arson by persons still unknown. Hitler, who had been chancellor for less than a month, immediately used the fire as a pretext to essentially end freedom in the country. The threat of something similar here is my worst nightmare about what may be ahead for us.

But another key message for us today came just four days after the death knell of German democracy and four thousand miles from Berlin, when Franklin Roosevelt, assuming the presidency, transformed the mood of our own nation and set it on a fundamentally different course. Roosevelt, too, held out the possibility of ultimately asking for “broad executive power to wage a war against the emergency,” but first and more importantly he urged the country to share his faith in the Constitution and that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

Fear is not only the thing we have to worry about today, but it may remain the most significant. And a critical task for the press will be to refrain from engendering fear—FDR called it “nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror, which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance”—unless and until that is merited. In an important sense, this is just Aesop’s fable of The Boy Who Cried Wolf as applied to journalism. If we hope to be believed in the moment of maximum danger, we need to take care not to assert that it is at hand prematurely.

What we should track this time

One practical way to begin. During the first Trump presidency, the Washington Post usefully, and exhaustively as well as exhaustingly, charted the President’s false and misleading claims, eventually clocking them at more than 30,000. I don’t see any value in repeating that exercise, not because Trump has reformed, but because the point has been made, and even most of Trump’s supporters get it.

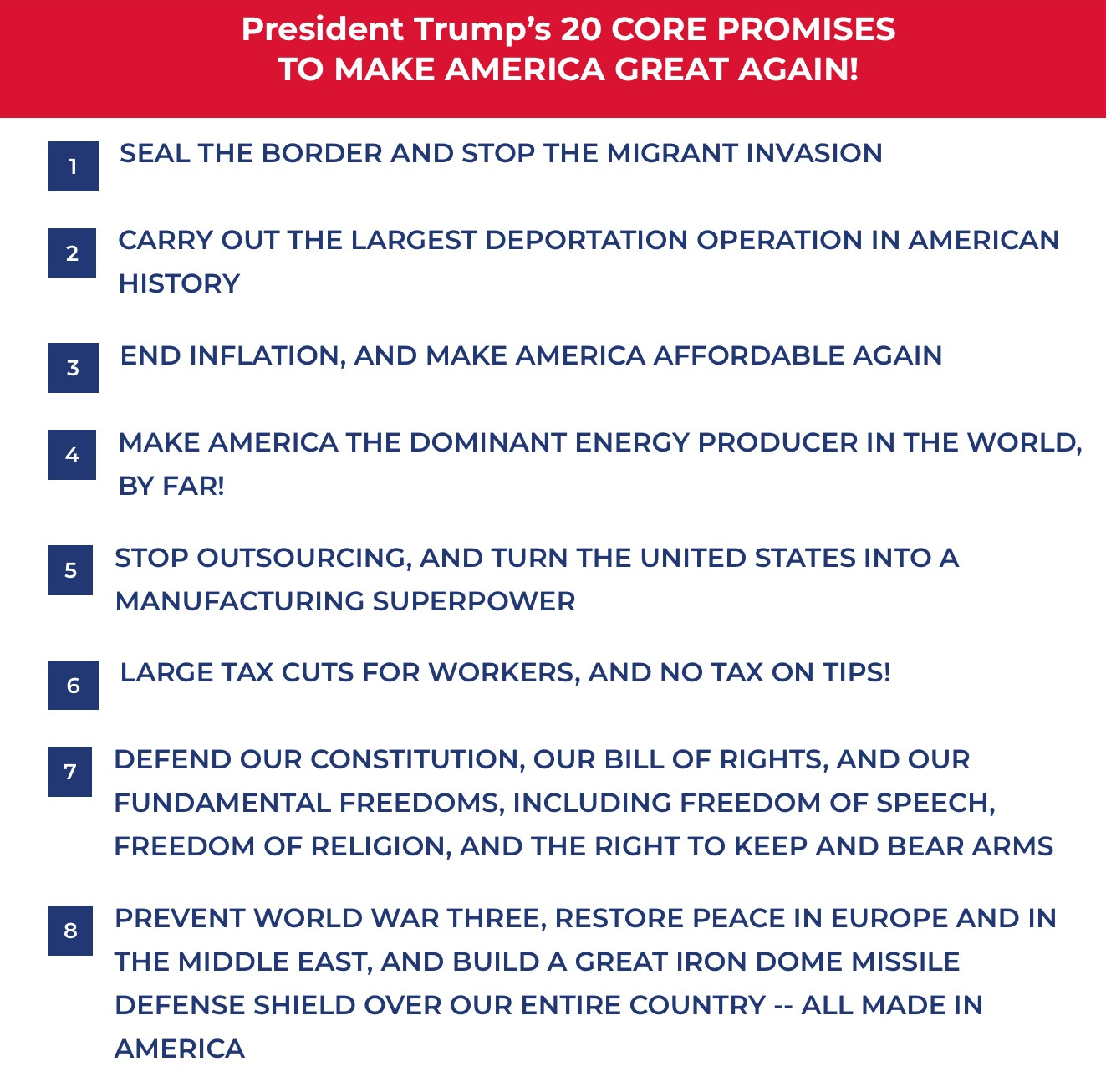

I do think, however, that we could very much benefit from an analogous effort to chart Trump’s record on keeping the promises he made in the 2024 campaign. Already, for instance, Trump seems to have abandoned his pledge to eliminate the Department of Education, nominating someone to head it. Will he be able to bring peace to Ukraine and Gaza before the end of this month, as he repeatedly insisted he would? How many deportations will occur, and how will they compare, for instance to the count under the Obama Administration? Is inflation ending (as Trump pledged), remaining stable or actually rising again?

One of the most interesting foreseeable stories of the year will be the necessity of passing a major tax bill, as the Trump 2017 law—the sole major legislative achievement of his first term—sunsets. Trump has promised well more than he can likely deliver here, and in ways that voters, in this case, may not have understood. Will he really eliminate the taxation of tips, overtime pay and Social Security payments, and increase the deduction for state and local taxes? Will the bond market constrain his ability to explode the deficit in the absence of an economic crisis? These sorts of questions may be the most useful framework for covering this running Capitol Hill story. (And there’s a great book to be reported and written here by the right journalists, a companion piece to this masterwork on the 1986 tax bill.)

What about the business of journalism?

Closer to home, in our own business, the two key metrics to watch remain audience and revenue, and I have lots of questions. Will there be a second Trump Bump in one or both? Will the over-extension of key institutional funders in 2023-24 result in increased difficulties for newsrooms in 2025? Will a lack of return on investment in terms of audience growth at some previously-favored newsrooms finally cause a revenue reckoning? Will more newsrooms start to learn from creators about the keys to building audience in our time? Will there be more consolidation in nonprofit news?

Turning to content, will a hostile regime in Washington chill journalism or spur it? Likely some of both, and it will be critical to note the distinctions. Will there finally be significant product innovations employing artificial intelligence? Will newsroom leaders be able to resist the drumbeat of Trump’s distractions and set their own course, or will he resume his place as the nation’s de facto assignment editor?

I look forward to learning the answers along with you, to watching the passing parade and trying most weeks to make some sense of it. Thanks ever so much for coming along for the ride.

Love your thought about focusing on the promises. It seems to me we often get distracted from the followup--'oh, there is a new regulation or law, it's been six months, how is it being enforced? What does that mean for people?' We often are chasing the next news item. Implementing stuff is often not very interesting material for stories.

Thanks for this, Dick. It’s up to main stream journalists to decide whether to provide coverage that challenges or turbo charges the worst of what lies ahead. The Founding Fathers created a system that assumed the former - let’s hope they were right.