Let’s Stop Trying to Hold Back the Future in News

Three mistakes we need to reverse on AI, Tik Tok and zombie local papers

Welcome to Second Rough Draft, a newsletter about journalism in our time, how it (often its business) is evolving, and the challenges it faces.

The news business was once pretty stable, but for the last 30 years that simply hasn’t been the case. First came the consumer Internet and the Web, then consumer broadband, followed by the rise of social media, the shattering of the business model and the emergence of nonprofits, revolutionary developments in the approach to data, audience and engagement and product, the increasing prevalence of true multimedia and most recently the consumerization of generative AI.

One of the key lessons of this dizzying succession should have been that clinging to the past, or trying to hold back the future is a fool’s errand. But I continue to be surprised by how much those attitudes remain prevalent in our field, and this week I want to call them out a bit.

Unsafe at this slow speed?

I was struck last month, for instance, by the contrast between what was happening inside OpenAI and how most newsrooms have behaved during the year since the public unveiling of ChatGPT. Inside the company, apparently, there was something approaching panic that things were moving too fast, at an unsafe speed.

But in most newsrooms, one year into what is pretty evidently a revolutionary development, experimentation has been stunningly modest, with the bulk of attention going to what are clearly transient problems with accuracy as these products mature and a few desperate efforts by cost-cutters to replace uninteresting content generated by humans on hamster wheels with uninteresting content generated by machines. I am certainly not advocating leaping before looking, but it’s possible to do one and then the other in the proper sequence.

I hope 2024 will start to bring the exciting AI innovations in versioning, graphics and art, data analysis and much more that are fairly evidently within the grasp of those who have the courage and vision to reach for them.

Pivot to Tik Tok?

The same sort of reluctance to embrace the future, it seems to me, can be seen in the very muted reaction in journalism circles to what I saw as one of most significant data points to emerge in recent months: Pew, in one of its authoritative studies, revealing that more adults now get news from Tik Tok than Twitter. Nor was this shift due primarily to the decline of Twitter under its anti-Semitic edgelord owner. Twitter declined from being a news source for 14% of adults in 2022 to 12% this year, but Tik Tok grew more than Twitter shrunk, rising from 10% to 14%.

Yet, there seem very few major newsrooms, even now, who devote as much energy to Tik Tok as they do to Twitter, even as this shift will almost surely require more work, at the very least in creating promotions for stories—and ideally versions of them-- consonant with Tik Tok’s user preferences, mores and behaviors. Twitter demanded short text versions of what were mostly still text stories. Tik Tok requires an embrace of video even from newsrooms whose core work remains centered in text. And its quick emergence should prompt not another heedless “pivot to video,” but surely a creative and thoughtful reassessment of how the news can most effectively be presented to new and especially younger audiences.

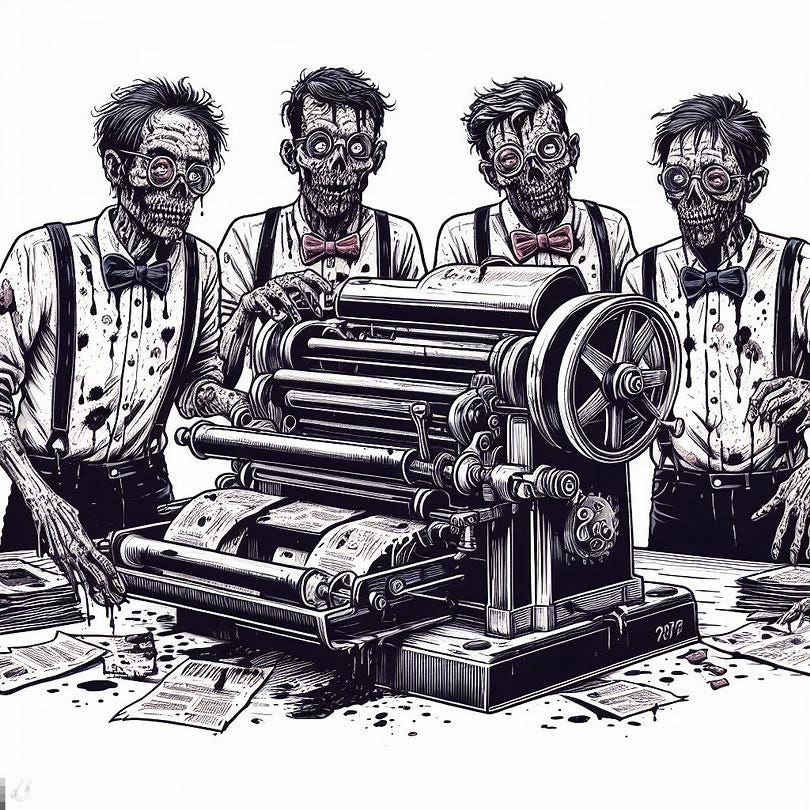

Please don’t feed the zombies

The third alarming development I want to spotlight this week goes beyond trying to slow-walk or ignore the future to what I see, in some quarters, as a temptation to find refuge in an embrace of the past. Mostly, this revolves around local newspapers, especially those that have already been reduced to near zombie status by the hedge funds that control them. Behind the scenes, I am seeing signs that people who should be focusing on creating the future of news are instead still fixated on how these papers can be rescued—through tax breaks or nonprofit conversions or roll-ups.

That approach isn’t compelling to me. It threatens to devote an inordinate share of scarce resources to properties that have forsaken their communities, to focus the betting on franchises many of which are likely beyond effective revival.

I am not talking here about still-thriving papers in places like Boston, Minneapolis, Seattle, Atlanta, Philadelphia and elsewhere (even while acknowledging that the strength of these franchises continues to erode somewhat). They are still the leaders in their communities; their best contemporary work is still among the best in their illustrious histories.

But beyond these relatively few properties, it’s important to remember that the larger project in which we are engaged is trying to save the news in this country, not the salvation of particular news organizations in cases when they have ceased to merit the loyalty that would entail.

Such a mistaken focus would replicate the error of those who, at an earlier stage in the digital revolution, thought what we needed to do was save the elite print papers and investigative reporting. That has been largely achieved, albeit not in print and with a major assist from nonprofits, but the business crisis of the press not only persists, it deepens.

It thus no longer makes sense, if it ever did, to define “news deserts” with particular reference to the disappearance of newspapers or by ignoring local broadcast television— which remains the leading source of local news, no matter how limited. But this isn’t a narrow methodological point about very solid academic work: it’s a concern about a mindset that might respond by mistakenly concluding that slowing the disappearance of newspapers, without more, is a critical policy goal.

It has been a very challenging 20 years in the news business; I know why people can feel like their default posture should be a defensive crouch, occasionally warmed by nostalgia. But as an industry, that’s not where we need to be. We are re-inventing news— that’s the opportunity, and it can even be the fun. To make the most of the opportunity, we need to embrace the future with urgency and determination. And with a zest for experimentation and change.

Sometimes funders are criticized for supporting nonprofit news. Commercial outlets say it is wrong to finance "competition." That's not how I see it. The Titanic is sinking and there are not enough lifeboats. If you send more lifeboats, that's not competition. It's a rescue.

Great piece and terrific graphic!