Journalism and the Unmaking of Elon Musk

Suspending skepticism for the very rich leads us into error.

Welcome to Second Rough Draft, a newsletter about journalism in our time, how it (often its business) is evolving, and the challenges it faces.

Second Rough Draft was going to take this week off, but after last night’s Twitter fiasco, I just couldn’t resist. We may take next week off instead.

In September, Walter Isaacson, biographer of Steve Jobs, Albert Einstein, Benjamin Franklin and Leonardo da Vinci, will publish a book about Elon Musk. Perhaps when Isaacson began work three or so years ago he thought that Musk belonged in this collection of innovative geniuses. Now, however, his publisher says the new book will depict “a tough yet vulnerable man-child, prone to abrupt Jekyll-and-Hyde mood swings, with an exceedingly high tolerance for risk, a craving for drama, an epic sense of mission, and a maniacal intensity that was callous and at times destructive.”

In other words, Elon Musk, as we have all pretty much discovered since he took over and ruined Twitter, isn’t who many had believed him to be. This week I want to explore how that happened. That is, I want to talk about a failure of journalism.

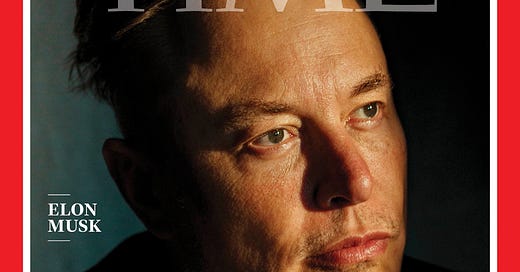

The high water mark of this failure was almost certainly the story, just 18 months ago, designating Musk as Time’s Person of the Year for 2021. That piece said that Musk “harnesses the sun” and “bestrides the Earth,” and literally called him a “man-god.” It had its share of caveats, but assured us that “the vast expanse of human misery can seem an afterthought to a man with his eyes on Mars.” One conservative think-tanker was cited for the proposition that, “Musk does have a coherent politics, whether or not he articulates it. ‘It is a politics of progress.’”

Not quite.

In an interview with Time, Musk, “our avatar of infinite possibility,” predicted that his Starship would orbit the Moon this year. At this writing, it’s quite unclear if it will orbit even Earth. Time celebrated Tesla’s trillion dollar market capitalization. Today, the Dow has fallen about 11% from the story’s publication, while Tesla’s valuation is down more than 40% from that vaunted milestone.

A friend got to lionize Musk as “the most viral social influencer ever;” the lead of the Time cover story displayed amusement with his live-tweeting of a bowel movement. Now Musk depends on bending an algorithm he purchased to amplify his own voice and mute those of others— that is, when his inept management hasn’t caused the platform to crash.

It wasn’t just Time, of course. A year earlier, Fortune—which had been under common control with Time for almost 90 years after its launch, but has been separately owned since 2018—made Musk its Businessperson of the Year for 2020. And it wasn’t that the journalists involved didn’t know better: the Time cover piece which used the phrase “man-god” also noted poor working conditions and unfair labor practices at Musk companies, allegations of sexual harassment and adverse judgments on race discrimination, a settlement in a case charging securities fraud, huge dependence on corporate welfare and tax breaks, and 17 injured and one killed by Tesla’s Autopilot.

What to make of this almost willful blindness to cruelty, bigotry and nihilism, to excusing the destructiveness of a grown man as so many temper tantrums?

How the rich are different

A big part of it lies in the credulousness of so much of the press when it comes to people of great wealth. We are constantly making the mistake in this country of assuming that people who are extraordinarily successful in a particular line of business must be simply extraordinary. The reality is very often otherwise.

Even Donald Trump’s defenders acknowledge he turned out to be a lousy public manager, firing a modern record number of cabinet officials he had himself appointed, and unable to build most of the border wall he promised. Bill Gates saw himself as qualified to steer the country’s education system, used his money to try to impose that vision, and met with repeated failure. In our own industry, Jeff Bezos has subsidized the Washington Post, but also failed to bring it any important technological or marketing advantage.

Even claims of business success—without any there there—can often be enough to get reporters to suspend their usual skepticism. I wrote a while back about the fiasco of covering Andrew Yang, a candidate ostensibly on the left. We are now perhaps in the early stages of repeating many of these same mistakes with Vivek Ramaswamy, this time ostensibly on the right.

Scott Fitzgerald wrote almost a century ago that “the very rich… are different from you and me.” But Hemingway was more nearly on the mark when, a decade later, he had a character retort, “Yes, they have more money.” Fitzgerald was an outstanding novelist, one of our best. But Hemingway, with his own flaws, was also a great journalist. It is his skepticism, his intolerance for cant and hyperbole, that journalists need to bring to their work, especially in the coverage of those who would be transcendent figures.

Another savvy column, Dick. I found the DeSantis campaign launch event especially disturbing. Elon Musk described “the legacy media” as “something like five editors of newspapers…a tiny elite cabal” & Twitter’s mission in part to dis-intermediate America’s leading major news organizations and in so doing to save us all: “Twitter was expensive,” says Musk, but “free speech is priceless…”

How long before "That was insane, sorry" becomes the apology of choice for the power set? But I digress from the point of this trenchant column. You have hit on a tension in journalism made worse by the attention economy--we extol people for reasons that often turn out to be eclipsed by circumstance, but when people are consistent, their story doesn't change much, making it hard to engage readers with something new about them. Also, readers can become uncomfortable when comparing themselves to the person, what Tracy Kidder and Dick Todd called "the problem of goodness." A note on Gates: at least in his tech days, he would attribute his success in part to luck (in part).