Welcome to Second Rough Draft, a newsletter about journalism in our time, how it (often its business) is evolving, and the challenges it faces.

Whatever you think about the debate on objectivity in journalism, I think we can all agree that the most basic responsibility of the press in our society is to inform the people so that they can exercise their democratic rights. It seems increasingly apparent to me that we’re not meeting that responsibility very well, although the problem may not lie where you think. That is to say, the heart of the problem is not about Donald Trump.

Inflation is falling, and is currently just over 3%, which is above the Fed’s target of 2%, but hardly high by any reasonable definition, and down by more than two-thirds from its peak in 2021. Unemployment is 3.5%, which is historically low by any standard. Wages are growing faster than inflation. Deaths from COVID are now less common than those from the flu or kidney or liver disease. Crime nationwide remains at historically low levels. The number of immigrants in the country illegally has continuously been roughly flat since George W. Bush was president. The stock market is within 6% of an all-time high. (If you are looking for an indicator of more parochial interest, even digital advertising appears to be ticking up in many places, per recent corporate earnings reports.) Meanwhile, the Chinese economy is in trouble, and Putin faced an attempted coup while his own economy and position in Ukraine slowly deteriorate.

The disconnect

Those are the facts. How do Americans feel about them? Two in three think the state of the economy is bad, even though a large majority describe their own situation as good or excellent. Opinions on the health of the job market are about evenly split, even as many employers beg for workers and raise wages to attract them.

How does all this relate to the press? Look at this CBS poll on the economy: It tracks inflation by asking people if they think prices are rising. Of course they do. Even when inflation is 2%, prices are rising; they are almost always rising. Indeed, if they were actually falling on a sustained basis, that would be deflation, which is a symptom of a very sick economy, and something essentially all policymakers seek to avoid. Prices are rising, but inflation, as noted above, is falling—pretty quickly, and quite a bit.

Meanwhile, the widely expected recession has failed to materialize, the job gains continue, and purchasing power is growing as inflation recedes. More jobs have been created in the two and a half years since Biden became president than in any full presidential term in modern history. The only presidents who saw more job creation were Clinton (eight years), Reagan (also eight) and FDR (12-plus).

Amid this, we marvel that news avoidance is growing, as people tune us out. In reporting this, the Washington Post observes, citing no sources, that “it’s hard on any given day to find much news that can be described as ‘positive’ or ‘uplifting.’” Really? How hard are we looking?

And whose fault is that?

If the American people literally don’t know what’s going on around them, shouldn’t we be asking more urgently how we can do a better job of informing them? Is a significant part of that perhaps that we have been far too reluctant to compellingly report positive developments?

Interestingly, while the rise of Donald Trump is often held up as an example of press failure (a concern I have shared), the facts about Trump seem to be becoming much better known than those about the economy, crime, immigration and perhaps even COVID.

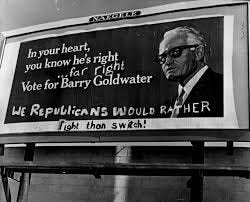

Before diving into this, let’s set a baseline. Partisan opinion in this country is always sharply split. In the most lopsided two-party presidential elections in our modern history, the losing candidate always receives about 40% of the vote. That’s roughly what Alf Landon got in 1936, what Barry Goldwater got in 1964, what George McGovern got in 1972, what Walter Mondale got in 1984-- when FDR, LBJ, Nixon and Reagan were overwhelmingly re-elected. (At the time of the Reagan landslide— “it’s morning again in America” was the tagline— unemployment was 7% and inflation was 4%.)

In the context of the limits of consensus, then, it’s striking that a majority (51% per the New York Times in a poll taken after his first two indictments but before the two more recent) think Trump has committed serious crimes, while 52% in an ABC poll, 53% in an AP poll and 54% in an Quinnipiac poll say he should have been charged in the federal election case, even when he has not yet been convicted and we are taught about a presumption of innocence. Trump’s favorability rating is actually right at the 40% marker representing the minimum possible vote we could expect him (or any other major party nominee) to receive next November.

It’s not 2020 anymore

What are we to make of all this? I think one of the most common mistakes these days in considering so many aspects of life in this country is to underestimate the trauma inflicted by the pandemic and the other events of 2020, including the murder of George Floyd and its aftermath.

The press, too, may be suffering from a version of PTSD. Our only choice, I believe, is to work through that. Part of the answer will lie in recovering our confidence. That very much includes the confidence to tell people the news forthrightly, even when it is good.

As always, totally spot on.

Excellent and important points, Dick.