How to Cover a Normal Presidency

A slower pace of news, a more strategic approach to leadership-- it's time for a different kind of coverage as well

Welcome to Second Rough Draft, a new newsletter about journalism in our time, how it (especially its business) is evolving, and the challenges it faces.

Throughout the presidency of Donald Trump, reporters found themselves typing the sentence “This isn’t normal.” They typed it into articles, tweets, television scripts, typed it far more often than should have been necessary, perhaps more than was necessary. But it was true. Trump took delight, for reasons I am not sure we yet really understand, in not just innovating in the presidency, but in breaking up the furniture, some of it just traditional and customary, some of it importantly institutional, ultimately some of it constitutional.

Trump may yet return—although I very much doubt it—but for now normality[1] has been restored in the American presidency. Citizens seem pleased; President Biden’s approval ratings in most polls markedly exceed his share of the vote that elected him, something Trump never achieved. But some elements of the press are having a hard time adjusting.

Recognizing normality

How can we be sure normality has resumed? The signs abound: to the extent the President’s agenda is in tension with his official duties the tension comes from his political interests, not his business interests; cabinet officers seek to bend their agencies to the administration’s will, not undermine the agencies altogether—the executive branch is no longer at war with itself.

For journalists, two big things have especially changed. First, the pace of news has significantly slowed. Yes, an enormous piece of legislation moved through Congress in 50 days, but that was nearly the sole legislative focus—especially after grappling with Trump’s tragic and farcical last-minute attempt to overthrow the government. Yes, the vaccine rollout and seeming waning of the pandemic are monumental events.

But it is often possible these days, as it simply was not for the last five years, to fairly accurately predict tomorrow’s news agenda today, and even next week’s news agenda this week. A stray tweet is unlikely to upset such predictions. One result is that those “BREAKING NEWS” headlines on cable, long over the top, are increasingly ridiculous, more frequently neither breaking nor news.

Second, the business of the presidency is being conducted with strategic intent and notable discipline: roll out vaccines, pass the Rescue Act, then try for an infrastructure bill, continue to angle for some sort of filibuster exception to enact HR 1, try to keep most other things off the front burner. All of this is being done in plain sight. Such a strategic approach has the effect of reinforcing the slowdown in the pace of news, and can be especially frustrating for people whose job is to fill a daily (or more frequent) newshole.

What is to be done?

How should journalists respond?

Rather than mourning the lost constancy of the abnormal (leave that to the advertising department), we can recognize that there is an opportunity to be seized. If there are fewer genuine twists and turns in politics, pay more attention to governance. That is where the action has always been anyway, even—or perhaps especially—because much of it takes place outside of Washington.

History will, after all, judge not what is announced, but what actually occurs. How is vaccine rollout going? Where (and for whom) is progress being made, and where (and for whom) not? How effective is the Rescue Act in creating and saving jobs, and reopening and rebuilding the economy? What are its unintended consequences? Its intended but unheralded impacts?

This gets to a big piece of what Trump never understood, and about which I think he ended up confusing many of the reporters covering him. Facts still matter. It mattered that people lost their jobs, or their lives, and didn’t matter nearly as much when he tried to pretend that they hadn’t, or even to just change the subject.

Beyond this, it’s important that journalists not get confused and think the story is about them when it is not. When the president of the United States constantly referred to the press with the authoritarian term “enemy of the people,” that was a real story. When Biden prefers to have his press secretary take questions than to do so himself, that is not. Nor was it newsworthy when the previous regime did the opposite: having the president answer questions constantly, while abandoning the press room podium for months at a time. The issue is whether the American people’s questions about the operations of their government are being answered. The truth is that the answer was “yes” under Trump and is again under Biden. Whether the answers make sense is a separate matter.

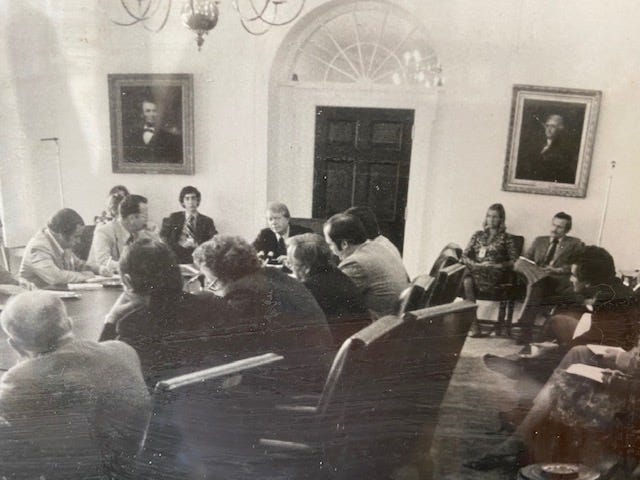

Forty four years ago, I worked quite briefly in a very junior role in the White House press office. I then wrote my undergraduate thesis on the history of White House press relations A lot has changed since then, but some important things have not. The White House is a tough beat. Unlike Congress, there are no halls you can freely walk. In the more effective administrations, and many new ones, there are few staff factions to play off each other for sourcing. The news flow can be relatively easily managed by the newsmakers, and often is. The result is that the reporters with the greatest access to a president are often those most frustrated in their reporting.

None of this was true in the last four years: factions were constant, news flows were chaotic, leaks were endemic. It must have been disturbing to watch up close, but also thrilling, the place to be.

Now, again, it is not. Once again, as often before, the coverage of a normal presidency needs to be re-centered, with the aperture widened, away from a tight focus on the chief executive personally and toward the government he leads and the people he is sworn to represent. Covering the presidency, we are being reminded, shouldn’t just be about the president.

[1] Not, please God, “normalcy,” even in the context of the presidency, no matter what Warren Harding stood for.