Bringing Digital Democracy to California and Beyond: A Conversation with Neil Chase of CalMatters

Enhanced database can be both a model and perhaps a revenue source

Welcome to Second Rough Draft, a newsletter about journalism in our time, how it (often its business) is evolving, and the challenges it faces.

One of the most interesting recent developments in local news, I think, has been the expansion of Digital Democracy, a tool for government accountability in California published by the newsroom CalMatters. Digital Democracy, first created by a think tank at a state university, moved to CalMatters three years ago, and a 2.0 version began development in 2023 as a joint project of CalMatters and CalPoly San Luis Obispo, the original sponsor.

It launched last April, and includes data visualizations for all 120 California state legislators, tracks 2000 bills per year, includes more than 1600 hours of video and takes significant advantage of AI, as you will see below. It had more than 800,000 users in 2024. I recently talked about Digital Democracy with Neil Chase, the CEO of CalMatters. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

RT: Neil, thanks again for doing this. Can you first describe the current scope of the information contained within Digital Democracy?

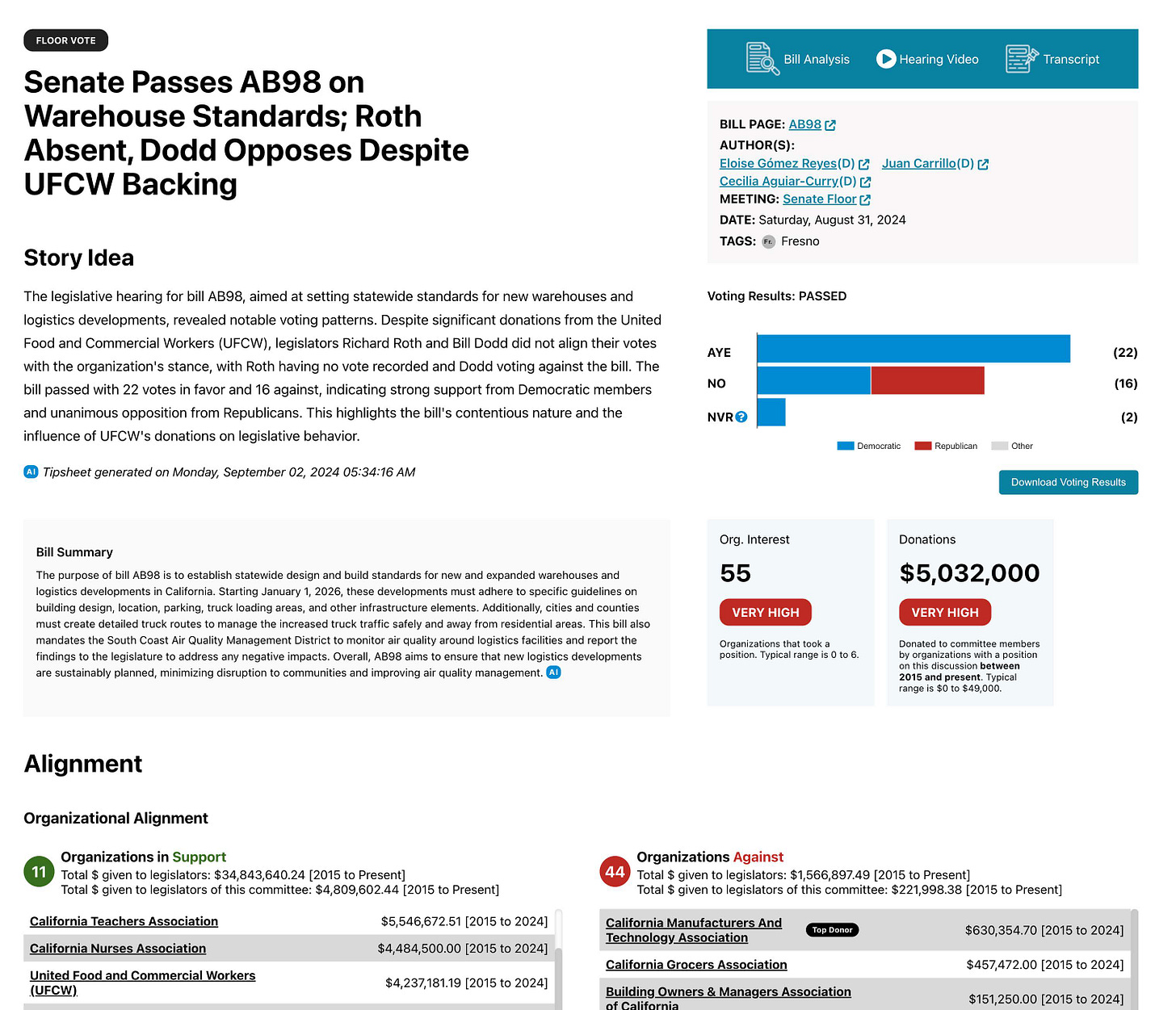

NC: We have about one hundred different data feeds coming in. Everything that we have is actually public information, almost all information that is created and made available by various government agencies. We also have the ratings that interest groups compile for the members of legislature, and every dollar donated to a member of the legislature.

We have all the campaign finance data and history, the video and transcripts of every floor session and committee hearing that has happened in the legislature in the past several years. We have voting records on bills, and when a member asks someone to donate to a charity on their behalf.

Almost all of it is pulled in through various scripts and bots that collect this data and keep it up to date. There's one body of information that is only available on handwritten forms, which is gifts to legislators. Somehow, they haven't gotten around to digitizing that; they're just PDFs. So we bring in the student staff of the Hornet, the newspaper on campus at Sacramento State, a couple times a year and give them pizza and twenty bucks an hour to digitize the data.

RT: Is it correct to say that the data is mostly organized by legislator?

NC: It's a database. The legislator is one key organizing principle. We also believe people come in with interests in certain topics, so you can search by those. You can also look at an interest group.

RT: Can you give us a similar overview of the current usage of Digital Democracy?

NC: There's a use case that we knew would happen, which is the reporters and lobbyists who follow this stuff closely, they use it as a reference every day to track bills that they care about. They use it to identify which members of the legislature might be open to a conversation about a certain topic based on their voting history or their ties. They use it to understand what other influencers are doing in the legislature.

There's another use case that we hoped would happen but weren't sure about, which is individual people who care about a particular issue, who are going to go talk to somebody in the capital for the first time, or who are trying to organize neighbors and friends. This is exactly what we wanted.

And then, of course, we hear about teachers using it in classrooms with journalism and political science classes. We also know that not nearly enough people know about Digital Democracy yet, and the more we can get it out there, the more usage we'll see.

RT: Where does that leave aggregate usage at this point?

NC: We've been at about 150-200,000 sessions a month-- more, of course, in the weeks when the legislature is crunching on bills at the end of the season, a little slower when the legislature is out of session, There has been a bit of a pickup around election time. That one bothers me, because we have detailed information about incumbents, but very little about most challengers. We would like to do a better job of looking at all the candidates.

The other interesting thing about usage is that a majority of it is driven by Google searches for bill numbers. So somebody searches for a bill number, and Google sends them to us, which I think is appropriate and also a sign that we've done some good SEO work on this.

Now featuring tip sheets

RT: You also use it internally at CalMatters as a source of story ideas. How does that work?

NC: That is the new twist. The big thing we added in this version 2.0 is the ability to crunch the data that we've collected and look for anomalies. This is very similar to what reporters did manually back in the day, when there were literally 134 journalists assigned to cover the state Capitol, to be in the building from all over the state.

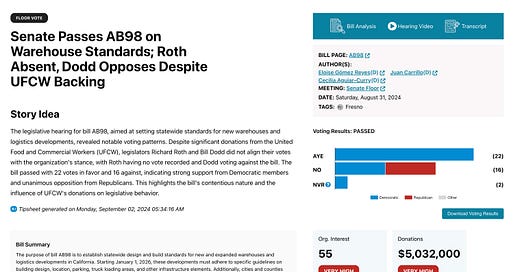

We now go through the data using AI. This isn't generative AI, but it is asking AI to crunch a bunch of data and look for anomalies-- for things like a member of the legislature who has been getting a lot of money from a certain interest group for a long time and has cast a vote today that was against that interest group's positions.

The legislature has a system where interest groups can register their positions on various bills, and we've got that data. So if you vote against your funding, or vote against your voting record, or vote no for the first time-- because many California legislators have literally never actually voted no on anything—we generate an alert.

We use the AI specifically to create what we call a tip sheet. It describes the anomaly, how the AI determined it, and why it got our attention. We have an alignment meter you can use to figure out which interest groups and legislators are more closely aligned or farther apart. For an active political reporter, it's a tip.

We think the real magic of it is that most local news organizations report very little about their member of the legislature. But if we can provide that tip sheet to a local newsroom, they might take the story and run with it. And we also want to serve the reporter who has to turn out three or four stories a day, maybe has an hour or two, by giving them all the information: here are some quotes, here's a photograph, here's the reasoning behind this, maybe even here are some phone calls you might want to make.

RT: Do you now provide these tip sheets to other news organizations?

NC: We do. We're rolling out carefully. We understand the potential for misuse of a tip that is not a vetted story. We have a password-protected site where they're available, and we are gradually letting other reporters around the state know about it, inviting them to spend some time with us, learning how it works, and then giving them access to that portal. We're working with six or seven newsrooms right now. We hope to be working with several dozen by the end of this year.

RT: A couple of quick background questions. You said there were once 134 journalists covering the Capitol. Roughly how many are there now?

NC: It's a little bit tricky, because we have a number of journalists who are covering legislative issues, but they're not physically at the Capitol. This was a physical presence back then. We did a photograph of all the journalists who were in the building at the end of the last session, about a year ago. There were 17, and that was on the last day of the session, the highest journalist attendance you're going to have in the legislature. Most often, there are five or 10.

RT: Of the 17, how many were yours at CalMatters?

NC: Four or five.

Going national

RT: And where do you stand on extending this concept to other states?

NC: It would be easy to say, hey, here's the open source code, go do whatever you want with it. But it's a lot of work and a lot of expense, and we don't expect that other newsrooms would be able to do this. My initial discussion with the developers was, can we expand this to city councils and school boards and water districts and county boards and everybody else who spends money? The answer was, that's going to be harder, because the data structure for Digital Democracy is two houses and a bunch of committees, and those other organizations are different. So the easier path to expansion is other state legislatures.

We're building right now for two states, Hawaii in partnership with Civil Beat and Texas in partnership with the Texas Tribune. Hawaii is less complicated: the legislature already posts their own videos on YouTube. And the Civil Beat folks have some very specific reporting goals. Texas is larger, more complex, and the Texas Tribune does a lot more reporting on different aspects of the legislative process, even than we do.

If we can add those two states this year, we should be able to add a dozen or even a couple dozen states over the next two or three years. The funders who are supporting this are Arnold Ventures, which supported it from the start back in 2015, and the Knight Foundation. Both of them are, of course, interested in seeing this spread to other states.

Paying the freight

RT: You've also said you see a revenue opportunity here for CalMatters, Can you talk about that?

NC: We didn't do this to make money. We're a nonprofit, but we do believe that there are probably some commercial applications of these tools. We never want to charge Californians for access to any news about California, and we hope we can make it free in other states as well.

But there are lobbying firms, there are corporate folks, there are people who just want to follow a bill in the legislature. We think that by creating different views of the same data, maybe some APIs so people can access it in different ways, different kinds of alerts, there might be revenue opportunities.

We've seen services in different states that do a little bit of what we do and are charging an annual or monthly fee, and we're trying to figure out how to generate revenue that would help pay for the work that we're doing without compromising the underlying fundamental principle of nonprofit journalism and public media, which is that we want to make this available to everybody who can use it.

The parallel piece is that we combined with The Markup last year, and they have some tools that also have some commercial application. Whether we build that inside of CalMatters, or we find the right partner externally, or we spin something off, I think there is potential commercial revenue that would support the journalism.

RT: Neil, this has been enormously interesting. Anything that I should have asked you, or that you'd like to add?

NC: It's an exciting thing to be able to do, but it does generate some internal questions among our own leadership and our Board about why would you do this outside of California? We are a California organization, but when you're covering California, you're covering one out of every eight Americans, and what we in California do influences the whole country. A lot of our readership is outside of California. But we have to make sure we don't let it drag us too far away from our primary goal of covering California. So that's my way of telling the Board, I heard you.

I founded and edit The Austin Bulldog, which is a one-man operation with an occasional freelance reporter. I created the Government Accountability Project to publish documents that local government agencies collect but can only be obtained with a public information request. https://theaustinbulldog.org/gap/ It currently contains nearly 8,000 pages of records obtained with more than 200 public information requests. It's searchable by the name of public officials. I could only dream of having the resources to automate things like Cal Matters, but their work is indeed inspiring.

Interesting to learn about this in detail. Even more interesting to see the parallels in: evolution, user behavior/segments and scaling potential w our (The Invisible Institute's) data products which focus on police accountability (cpdp.co).

Our 190,000 yearly users come most through folks searching individual officer names. We also have an important subsegment of public defenders, journalists and researchers. We too are looking at ways of scaling -- primarily through a new product which looks nationally at the question of exactly which officers work, and have worked, in which departments. (national.cpdp.co). But scaling is far from turnkey.

Top line, there is a big difference between data which is "available" to the public, through gov portals and FOIA and data that is actually useful to the general public in some simple basic way. Interestingly, making this translation relies on the unique, traditional skills of journalists. It requires deep knowledge of the system that produced the data (in our case, police depts) AND deep experience in what information folks need to guide their decision making and be informed.