A Smart Way to Subsidize Local Journalism, and a Less Smart One

Contrasting new rules for government ads with the case of public notices

Welcome to Second Rough Draft, a newsletter about journalism in our time, how it (often its business) is evolving, and the challenges it faces.

As journalism staggers under almost two decades of pressures on revenues, more attention, inevitably, turns to government as an alternative source—one with potentially enormous capacity. Lots of ideas are bubbling up under the rubric of “public policy,” some of them wiser than others. This week, I want to talk about two approaches involving advertising, one promising, I think, and one less so, as good illustrations of the care with which we need to approach this temptation.

Government spends a lot of money on advertising: urging people to take advantage of services (get your vaccines), recruiting employees (“the few, the proud, the Marines”), nudging people to behave better or obey the law (wear your seatbelt, drive more slowly, “just say no”) to vindicate their rights (insist on fair housing, vote!), seeking help in its own work (“if you see something, say something”).

In the past, the distribution of this advertising probably had as much to do with politics as with effective messaging. For instance, a 2013 report from what is now the Newmark Journalism School at the City University of New York found that city was spending 82% of its advertising money in the New York Times, which, then as now, served a quite limited proportion of the population (print circulation of the Times in the New York metro area in 2013 was less than 5% of the total population figure), but which had unmatched influence on office holders.

Progress in New York and Chicago

Prompted by the Charles Revson Foundation (disclosure: a consulting client of mine) and CUNY’s new Center for Community Media and its Advertising Boost Initiative, the vast bulk of the City’s $19 million advertising budget now goes to smaller local outlets. A similar program is in place in Chicago, at least under (now outgoing) Mayor Lori Lightfoot.

Safeguards are necessary here, especially against a new cronyism replacing the old. Ideally a content-neutral approach would place the advertising in all publications that were truly local (perhaps targeted against particular demographics, depending on the objective), bar it from being placed with national platforms or publishers, possibly limited to outlets above thresholds of minimal distribution and in proportion to their actual reach.

This kind of effort, if implemented locally across the country, could yield significant new revenues for the field. As public policy it makes sense. Mostly, the money would (at least ostensibly) need to be spent anyway. If the prices end up being a bit higher, that is a cost we have been willing to bear in all sorts of government contracting situations in order to achieve particular objectives (e.g. diversity, decent wages and working conditions, etc). The preservation of vibrant local journalism just joins the list.

Even at the federal level, it’s possible to imagine an analogous way to support journalism, for instance, by ceasing to place advertising with the hugely profitable online platforms and broadcast and cable television networks, and re-directing it, again in content-neutral ways. This could be accomplished by executive order. Federal spending on advertising alone runs into the hundreds of millions of dollars a year. Steve Waldman, now the leader of Rebuild Local News, has been recommending this for a dozen years.

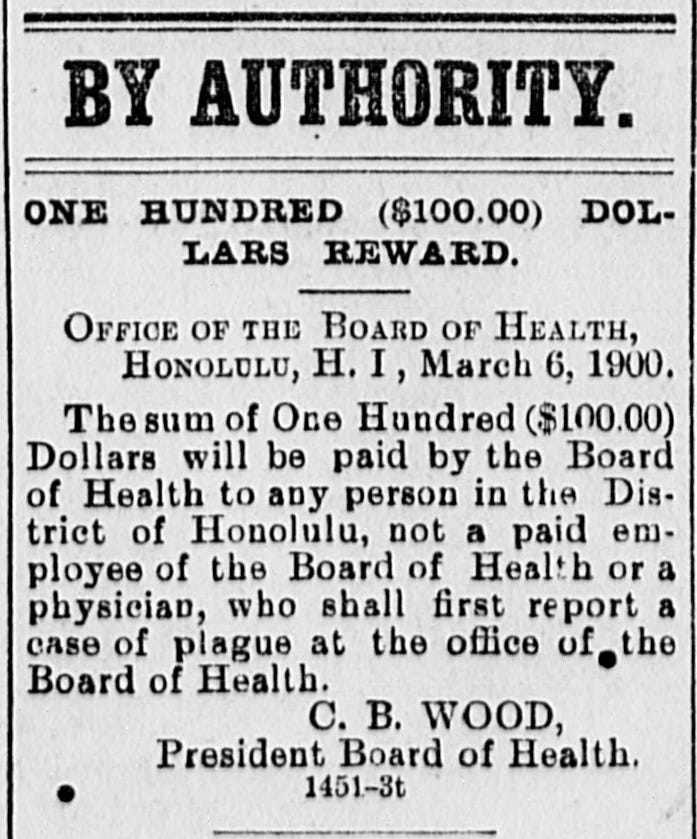

On the other hand

So far, so good. Now we come to public notice advertising, the dense, small type that used to run in the back of newspapers—and often still does. The purpose of this sort of advertising isn’t really to reach out to people, or to attract their attention. That’s why it’s devoid of photos or illustrations or slogans—all the advertising techniques developed over the last two centuries. Instead, as the name indicates, these postings are mandated by government and are intended to put people “on notice”—not because they saw them, but because, in theory, they might have. (A few actually do read them, but the evidence of this seems anecdotal, often drawing on the same anecdotes.)

In a digital world, such notices could be placed for free on websites, but they have for ages instead been required to be placed at significant cost in print newspapers. In this case, therefore, the subsidy is effectively 100%, in effect a special tax for the benefit of publishers.

There’s no question this system has kept a lot of small community newspapers alive—or that, conversely, eliminating it would harm them, likely bankrupting many. No matter how much we may regret that, the tide seems to be running in that direction. Public notices are being squeezed from at least two directions, especially from governments no longer willing to force this expenditure of private funds. A new law in Florida, for instance, signed by Ron DeSantis, will permit publication for free on government sites to be an acceptable substitute for paid notices in newspapers.

The second front has been opened by the friendlier forces of companies like Column, lead by former publishers, which has seen the handwriting on the wall here for years, and is trying to help newspapers to modernize and adapt if possible, while fighting a rearguard action against the deregulation of public notices.

Don’t misunderstand: I’m not eager for an end to public notice ads, because bad things will follow, news will go unreported, communities will suffer. The case for maintaining the notices, however, is strikingly similar to the cases made by most of what we often call “special interests” who get money from some government mandate that directly benefits only them. Yes, of course, there are indirect benefits, in the continued ability of local papers to provide community news, and I do value that, highly.

But as we craft a public policy agenda in support of the future of journalism, we need more creative approaches to shaping the powers and responsibilities of government that serve broader interests as well as our own—like New York’s Advertising Boost Initiative—and fewer that benefit only our own industry—no matter how critical it is.

Interesting. Thanks for posting!

I'm a very small one-person outlet that recently just took his first ad from a local government. It feels a bit strange, because I primarily write about local government. I know that I could use some guidance on what policies I need in place to assure it doesn't affect what I choose to report on. Today's post is very helpful.