Welcome to Second Rough Draft, a newsletter about journalism in our time, how it (often its business) is evolving, and the challenges it faces.

We’re presenting this week’s edition a few days early because, for the first (and perhaps last) time, it actually has some breaking news.

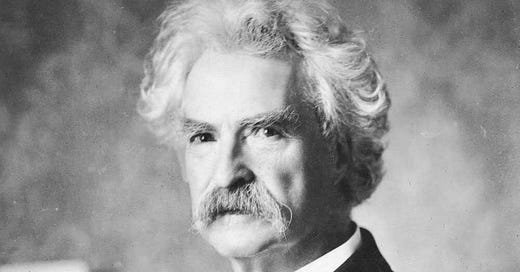

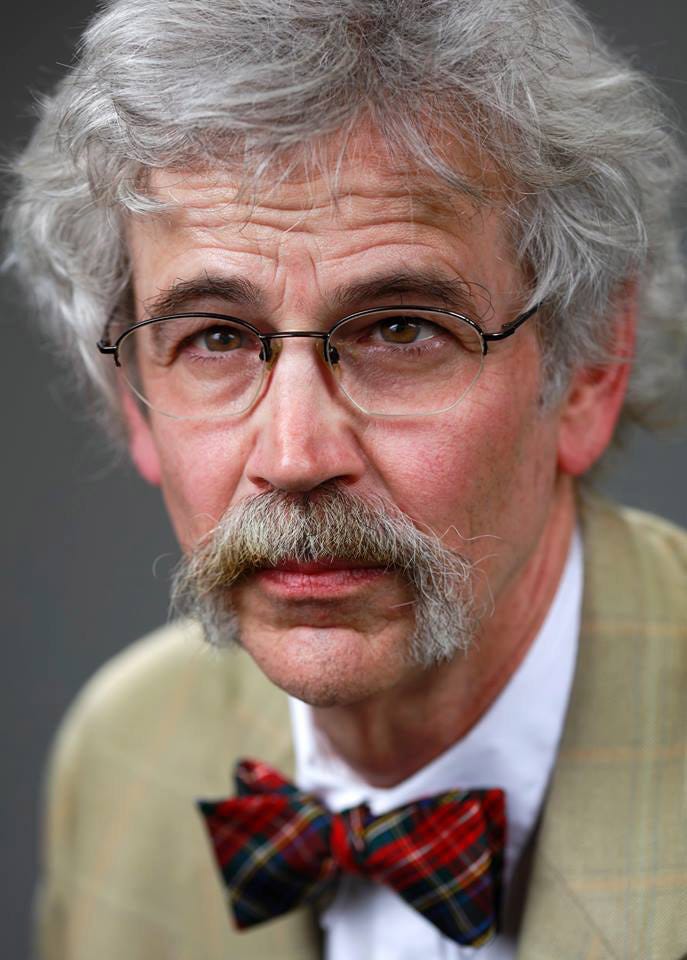

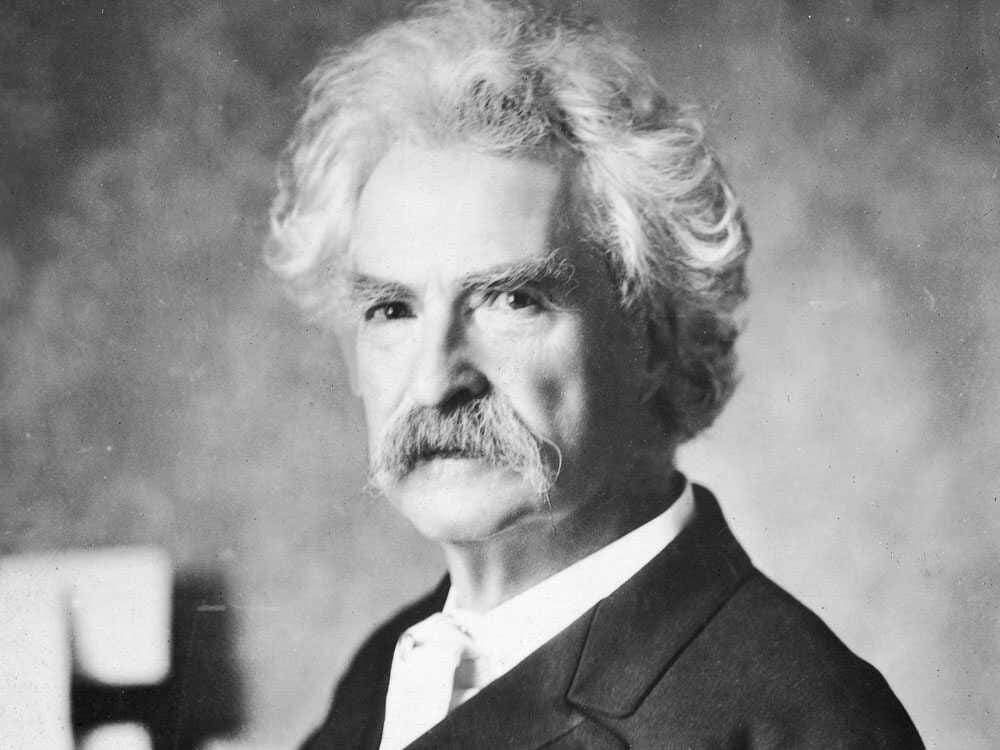

Almost all of us like a feel good story; many of us like scary stories. Last year’s film “Storm Lake” seemed to offer both, and the Concerned Journalism community—from pundits to funders—embraced it, with a national broadcast and more than 100 screenings across the country. The film tells the story of a paper in small town Iowa, the Storm Lake Times, struggling for its existence from 2018-20, while its charming editor, a Mark Twain lookalike who five years ago won the Pulitzer Prize for editorials, waxes eloquent on subjects from immigration to climate change to democracy.

The film poignantly ends with a card that reads: “65 million Americans live in news deserts—counties with only one newspaper or none at all.” At least twice in the film, the Times is referred to as Storm Lake’s “newspaper,” in the singular.

The problem with that, which went entirely unmentioned in the film and nearly all of the considerable hype surrounding it—from PBS promotion to film societies to foundation-sponsored screenings-- is that Storm Lake, Iowa doesn’t meet that news desert definition. It actually has two competitive English language papers, perhaps the smallest town in the country to do so. At least it did until last week (more on that last part later).

The stuff in the film about the Times and its editor Art Cullen seems to be accurate, and the film has no doubt done important work in raising awareness about the dire state of much local journalism. But what it left out is the Storm Lake Pilot-Tribune. The Pilot-Tribune (P-T) was founded in about 1870, the Times in 1990. The Times has had almost 3000 subscribers, the P-T almost half as many. The Times has a Storm Lake full-time equivalent news staff of a couple more than the P-T. Each sells for a dollar a copy at newsstands. Both appear twice weekly, although the P-T published three times a week until the pandemic. The P-T, which included a successful “shopper,” seems to have been consistently been more profitable.

The P-T doesn’t have a Pulitzer, but it’s not an editorial slouch. It won the general excellence award for medium size weeklies from the Iowa Newspaper Association in 2020. (The Times didn’t place for general excellence in that year’s awards, nor in those for 2021.) The P-T’s longtime editor, Dana Larsen, was cited by the association as a “master editor” in 2003, three years ahead of Cullen.

The P-T was Iowa’s newspaper of the year in 1988, just a year before Cullen’s brother, a former P-T staffer, decided to found the Times after the owners of the P-T declined to sell it to him. The Cullens made two subsequent offers that were also rebuffed, according to the Des Moines Register.

Oops

In the last week I’ve talked to a number of industry leaders who promoted the film nationally. None knew about the existence of the P-T. All were quite chagrined.

The reason those of us who aren’t Iowans might care about this, I would suggest, is that this film about journalism was actually a journalistic fail. People who watched it almost all took it at face value, and repeated its heartwarming—and misleading-- storyline as fact, without even the most cursory checking. If you’re looking for another reminder of why never to do that, just remember Storm Lake.

But the people knowingly complicit in it have harder questions to answer. Reached last Friday for comment about the film, Art Cullen told me, “I’m not a movie critic.” He says he never paid any attention to the P-T, and “don’t read it— never have.” As for the film, he said he “wouldn’t say it’s a misrepresentation” and thought it was “an accurate representation of the Storm Lake Times.”

Beth Levison, the co-director, told me that the card at the end of her film “wasn’t characterizing Storm Lake at all.” The P-T, she said, “wasn’t a factor” in the work of the Cullens “or their narrative.” She did say that the filmmakers had reached out to the P-T during filming, but had not heard back, and that they had “wrung their hands” about whether to include the P-T in the film, but had ultimately “made a choice” not to do so. I respect editorial and narrative choices, but the decision not to tell viewers even of the existence of another English language newspaper in town seems to me to have been a significant mistake. (The film does spend some time on the Spanish language newspaper in Storm Lake.)

Just Films, a Ford Foundation unit which provided the lead financing for the film, did not respond to a press inquiry directed to the Foundation on Friday. If they do, this post will be updated.

How about those who were merely trusting, or credulous in accepting the film’s implicit storyline of the town having one English language paper? Would it have been that hard to figure out the truth? No. If you Google “Storm Lake newspaper,” the second or third link is to the P-T.

That may be how the producers of this episode of NPR’s Fresh Air promoting the documentary knew to ask about “another newspaper” in town, although they did so 37 minutes into the 43-minute piece. (NPR may also have found out about the P-T from Art Cullen’s 2018 book, where it is mentioned six times, starting on page 5.) But NPR never identified the P-T by name, allowed Cullen to gently disparage it, and never acknowledged how its very existence undermined the premise of the film.

What about Independent Lens, which presented the film on PBS (with a rebroadcast scheduled for April 16)? Independent Lens did not respond to questions posed to a press representative on Friday. If they do, again this post will be updated.

And another thing

But wait, as they say on Vegematic ads, there’s more. I learned about the existence of the P-T casually from a fellow attendee at a local news conference last week, and started working on this column. Completely coincidentally (yes, that does happen), on Friday it was announced that the Times is buying the P-T, and folding it into the Times, which will become the Times Pilot. Art Cullen may not have read the P-T, but someone at the Times must have, because the press release Friday from the Times included a statement that this ends a “mini newspaper war” over three decades in which the “competition was fierce.”

The purchase price was not disclosed. The Cullens, whose pandemic gofundme for the Times was still $1200 short of its $30,000 goal at the time of the film’s broadcast in November, were aided significantly by what Art Cullen called a “generous donation” from California billionaire John Tu, who made his fortune with Kingston Technology, and who learned about the Times from that NPR interview and the film.

With the Cullens’ decision to close the P-T, Storm Lake the town will finally meet Storm Lake the film’s definition of a news desert. I hope the combination will be a good thing for the community.

Excellent writing. It's good to see there are still media critics in our midst. I realize that, like streetcars and passenger locomotives, there is a tendency to romanticize small-town newspapers and that's probably why this film made it through the usual fact-checking filters without any mention of the competition. As a boy, I visited Storm Lake with my folks who were attending a Presbyterian conference at Buena Vista University. All I remember from 50 years ago are fields of corn. By the by, it's funny to compare Times editor Art Cullen with Mark Twain but it certainly enhances the romance and comes with the territory.

Many Buena County residents are mourning the loss of Storm Lake's best newspaper, the Storm Lake Pilot Tribune. That paper has always been the most accurate, professional, and unbiased paper in the area, and the departure of long time editor, Dana Larsen, is a huge loss to our community.