A Forgotten Machine and its Lessons for AI in Newsrooms Today

What management and unions should learn from the story of linotype operators

Welcome to Second Rough Draft, a newsletter about journalism in our time, how it (often its business) is evolving, and the challenges it faces.

My first boss in journalism was actually the Print Shop teacher at my high school, a wonderful gentleman named Carl Riegert, who had once been a Linotype operator at a New York newspaper. (I think it was the Times, but am not sure about that.) He was a wizard in using the Linotype machine we still employed in those days to cast the text for our school paper in molten lead.

I have been reminded recently of Mr. Riegert, who died early in this century at 93, because of his career path, and because of a current controversy about AI. A number of newsroom union locals have banded together, and are demanding that employers agree that no jobs will be lost to AI. History suggests this wouldn’t be a wise move.

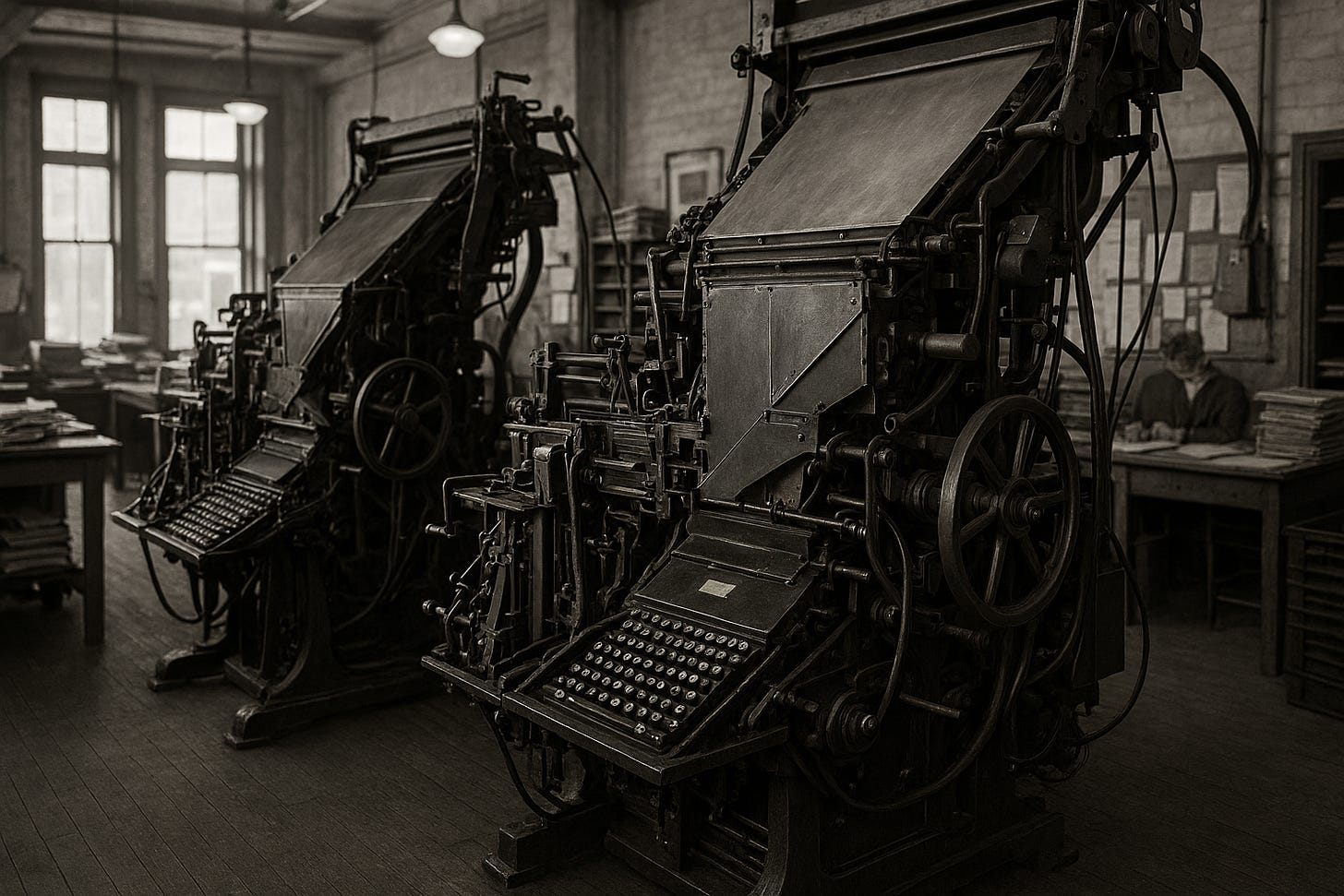

As this lovely piece from the Times recalls, Linotypes

cast one line of type at a time. At the stroke of a key on a peculiar-looking keyboard (the first two rows spelled e-t-a-o-i-n s-h-r-d-l-u), little brass molds dropped down chutes in an overhead magazine. Once a full line was assembled, the molds were shunted into a casting mechanism, where they received a dollop of molten lead. As it solidified, the lead line was ejected into a waiting steel tray, while the molds were recycled back into the magazine.

It took great skill to do the work quickly, and it was more than a bit dangerous, with an adjacent pot constantly melting lead at 535 degrees Farhenheit, and heavy new bars having to be hung over the pot from time to time. Sometimes a buzzsaw was employed to trim the molded lines—another scary operation, in which you could badly cut yourself quite easily.

What unions wanted then

New technology made the Linotype economically inefficient as early as 1964, and the Times sought to begin using computers to compose the paper that year. But a powerful union, known as Big Six, delayed that transition, first by literally ten years spent in negotiations around issues including eliminating the jobs of the linotypists. When the contract was agreed in 1974, it guaranteed lifetime employment to more than 800 workers at the Times and almost a thousand more at other New York papers.

Linotypes were then phased out over four more years at the Times, with 60 operators still employed on the last night of hot type production in 1978. (You can watch a wonderful documentary about that night here.) The last man to benefit from the lifetime employment guarantee retired in 2016; he had been hired more than a half century earlier, in 1965, when his job was already obsolete. He spent much of his career as a proofreader.

What it cost

Here’s the rub: In the period between when Linotypes were overtaken economically and when they were actually discontinued, the New York Journal American, Herald Tribune and World Telegram & Sun all went out of business. The loss to journalism, and to New York, was incalculable. The Times survived, but it spent millions, likely scores of millions if not more, employing people with skills it no longer needed. In a for-profit newsroom, some of that money might otherwise have gone to increased profits, but much of it can be measured in foregone news spending. In a nonprofit, such as many of those today’s unions are pressuring, all of the unnecessary cost would amount to news not reported or published.

Looking ahead

I do not know precisely which newsroom jobs AI will eliminate, but it’s certainly already possible to imagine much of copy editing and a good bit of graphic design going the way of linotyping. Other roles will surely also be implicated. All of us should feel sympathy for the people who hold these jobs. We should hope, fervently, that they find other rewarding outlets for their talents, just as I believe Mr. Riegert did. (He liked to joke, “It would be a great school, except for the students,” but he didn’t mean it; he seemed to love his teaching job, staying at it for nearly a quarter of a century, and a generation of editors of the school paper adored and deeply respected him.)

None of this should be taken as a call to use AI to write or report news, at least before it demonstrates a capacity to do so at the same level of quality as humans. That is certainly not yet the case and, in at least some respects, may never be. On the current state of technology, I think the rule of publishing nothing without prior human review is a wise one.

That said, what we should not do is to try to hold back the tide of history. It will make our industry weaker. And, ultimately, it won’t work.

Great evocation of newspapering history that should not be forgotten, and, as you say, has real relevance in the AI era. Thanks. Not that it matters, but you didn't mention the angry printersw' strike at The Washington Post, whose end left some people embittered against Katharine Graham even after her decisions to support Woodward & Bernstein and print the Pentagon papers. One other thing you didn't mention (although I'm not sure I have the facts rights) is that "e-t-a-o-i-n s-h-r-d-l-u" was transformed into a pseudonymic byline at some paper or other.

I enjoyed your article. Thanks.